The Blog

Blog Entry

Real Fine Now

For those readers familiar with Ezra Jack Keats through breezy little fables like A Letter to Amy and The Snowy Day, this writer and illustrator probably deserves a second, darker look. Maggie and the Pirate is a great deal harder to find than either of those titles and Whistle for Willie and all of the stories about Louie and his run-amuck imagination (more on those later), and it has nothing whatever to do with pirates, jolly or pillaging or otherwise, except that “The Pirate” is how a troubled little outcast wishfully identifies himself at the scene of a cricket-napping

And it’s not a ransom note he leaves either, but something like a desperate cry for help. This we find out after all of his scheming and stealing has gone tragically wrong, though it’s hardly the sort of mea culpa you are likely to ever witness on Playhouse Disney (“I just needed someone to love!!”) with soaring, explanatory music in background.

“They all sat down together,” is how Keats is content to leave us at the end. “Nobody said anything.”

Moody, marshy colors surround their quiet silhouettes, with here and there a desultory palm. From its beginning, this story appears to even promise a vacation from Keats’s familiar urban moonscapes – a dock, a raft, some ducks – though I think it becomes obvious pretty quickly that we haven’t traveled very far from the sort of working-class shadows where young children are forever in charge of supplying their own entertainment. Maggie and her parents even live in an old bus. That’s okay. At least Maggie doesn’t have to go to fencing classes after school.

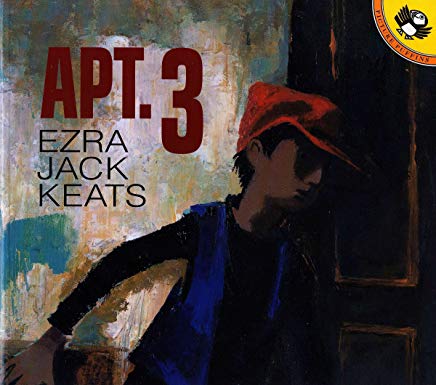

From a trailer park in Florida’s panhandle then, to public housing projects somewhere in New York, where Keats spent his own childhood, presumably inventing ramshackle playgrounds in his imagination before he thought to commit them to literature. These are sometimes unapologetically creepy on the page, and you wonder if Keats was not finally liberated to pursue this heart of darkness after gaining some earlier, commercial success. You wonder, but you’d be wrong, because there are everywhere these shafts of menace in his work – even The Snowy Day is not without its snowball-hurling “big boys” – and probably his scariest creation was a blind harmonica player (written relatively early in his career, in 1971) who emerges from out of the darkness of Apt. 3, snarling at two brothers who have come to find him out, this while all of the rest of the building gets on with its smoking, snoring, barking and bickering ways.

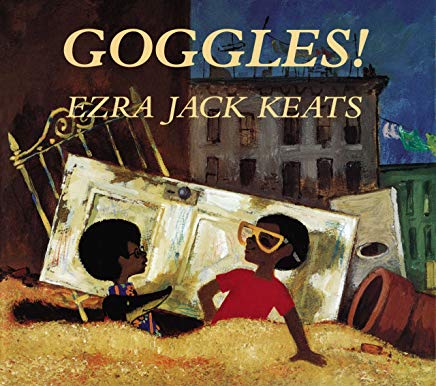

This man is redeemed – music has a way of transcending such darkness – though not so the bullies who appear from out of the wasteland in Goggles! to claim the sort of clunky Seventies eyewear that is never so modish as when you’re getting mugged. Peter – little Peter from The Snowy Day! – even thinks to raise a fist. That this seems dated probably says more about the constraints we are these days suffering in children’s recreation to nurture, instruct and ennoble than it does about the culture forty years ago – Mean Streets, all that. In fact, these hoodlums are every bit the worthy entertainment as a hideout constructed from doors ripped off their hinges and broken sewer pipes. As Archie, Peter’s nebbishy little friend, says, looking through those goggles at the end: “Things look real fine now!” And he’s not about to hit the slopes.

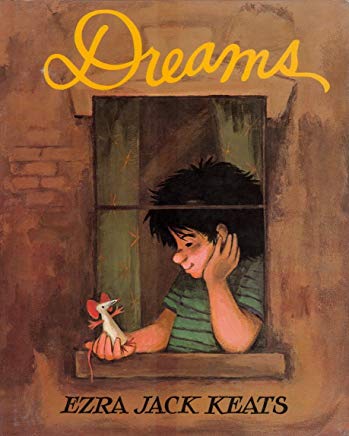

Discarded furniture is everywhere and incidental in each of these stories, the tenements identical, bricks falling out of walls, graffiti half-drawn, indeed what grows out of the windows in all this impersonal bleakness is often more luminously animated for being imagined – or privately witnessed – as Roberto, the resident insomniac discovers in Dreams.

Roberto is also a puppeteer, who returns four years later as a supporting player in Keats’s Louie, about a painfully reticent neighbor who appears so lost in his imagination that he becomes oddly, even uncomfortably attached to one of Roberto’s creations. What’s wrong with him? Is anything wrong with him? Keats isn’t saying, but you had to wait another five years if you were worrying – till Louie’s Search where he’s still spacey, still wandering, though now at least he’s talking, and now he’s got a bearded, scary junkman chasing him around.

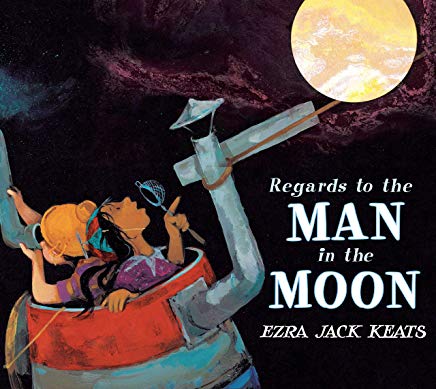

Who – fittingly – becomes his stepfather, and appears to give Louie some last, essential guidance in Keats’s final book, the great, phantasmagoric Regards to the Man in the Moon, where Louie gets to actually take a couple of passengers along for a ride – through rock storms and spectacular space stuff “and on through worlds no one had ever seen before.” He even rescues some stragglers from the doldrums of their own exhausted imaginations. Another weird trip. Amazing what you can make out of other people’s nothing.