The Blog

Blog Entry

Want Not

There was recently a very cool exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where a Chinese guy named Song Dong had collected all of his mother’s earthly belongings for display – from old magazines to un-recycled bottles to cooking pots to every single pair of baby shoes that Song and his sister ever wore. The mother – Zhao Xiang Yuan – died a few months ago, apparently while this exhibit was being planned, so she’d obviously agreed to part with all this stuff, after forty or so years of hoarding it in a house that must have been literally bulging, if the frame that was also a apart of the exhibit was even a quarter of its total size. Zhao Xiang Yuan lived through the privations of the Cultural Revolution, and so, the story goes, was loathe to part with anything potentially valuable in a way that we, as a generation of Americans accustomed to disposable plenty, cannot so easily fathom. But we can try. “Waste Not” was the name of the exhibit, it filled the entire mezzanine section of a pretty big building, and while my seven-year-old was quick to weigh in that he didn’t see how it was art, I think he was also relieved, and pored over the relics – one oven, one couch, dozens of basins, four successive generations of phonographs and televisions, almost-empty tubes of toothpaste, a mountain of half-used medicine, and enough chopsticks to build a small picket fence.

I’ll bet anything, too, that this collection will continue to occupy a larger place in his consciousness, and in mine, than whatever it was attracting people to that mezzanine a couple of months ago, and isn’t that the least we can ask of any art? This and some window to look upon the survival – the struggles and compensations and over-compensations – of, oh, about a billion of our fellow humans?

Intelligent people can disagree on their children’s abilities to begin to process the harder realities of whatever it is happening one county, one apartment, one continent away, but intelligent people have at their disposal very few means to try to even broach these difficult subjects, and it’s not altogether surprising when we chuck the whole project. The war thing, I know it’s kind of scary, and famines are such a bummer, still any little empathy we can conceivably arouse strikes me as more than a little worthwhile – morally, practically – especially if we have aspirations for our children that they will ever successfully participate in the world outside of our increasingly gated community.

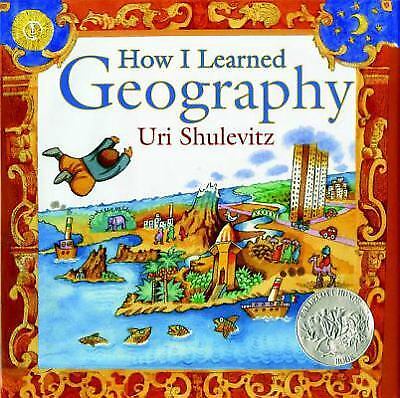

How I Learned Geography, by Uri Shulevitz, tells of a boy on the run with his family:

“When war devastated the land, buildings crumbled to dust. Everything we had was lost, and we fled empty-handed.”

Shulevitz himself moved from Warsaw (chased by bombs) to present-day Kazakhstan, then Israel and Paris before settling in the United States. In the story, some version of his father (to whom the book is dedicated) goes out to the market in what appears to be probably Kazakhstan to buy his family a loaf of bread – and brings back a map.

“No supper tonight,” Mother said bitterly. “We’ll have the map instead.”

That night the boy is furious with his father, as well as a loud-eating neighbor, though of course the map ends up nourishing him forever with it’s fantastical destinations – “Pennsylvania Transylvania Minsk,” he chants while imagining snowy mountains and wondrous, dancing temples and papaya groves. It also traces a path toward the pretty successful career of a writer and illustrator, as the boy (and the artist) set about copying and remembering bits and colorful fragments of the world as it appeared on his wall.

This book has done well, I think buoyed as much by the irresistible arc of the story as some imminent recommendations, but it too will disappear, and finally be replaced – by what? – on the shelves of our bookstores. To dream is admittedly a complicated matter – as much about what we hold onto as what we choose to forget - but here’s hoping that something as simple as our timidity does not become somebody else’s burden. Because they cannot find the future without a map.