The Blog

Blog Entry

Wait, We Just Got Here

Let us please consider Michael Rosen’s Sad Book, even if we do not end up reading it to our children. This would be understandable. I needed to recently track it down for myself to make sure I wasn’t hallucinating the first and second times I read it (in a rural, possibly make-believe library) and had a pretty hard time getting my hands on a copy till some showed up in a store near me where nobody appears to be very thoroughly vetting the inventory for dangerous characters like this. In fact, when I found it, the book had a business card clipped in the opening pages with a note from its publisher’s “publicity manager” from six years ago: “We are so excited

has been selected as an honor book. I understand you need three copies right away.” I don’t know what honor she was referring to (really, I kind of make it my business not to know these things), yet three copies there still were.

First, about the title: this is indeed a sad but unflinching and remarkably frank account of one father’s reaction to the death of his son. It sounds like these are impressions lifted directly from the author’s experience (or anyway, there’s no evidence to think they are not), in fact this entire unlikely endeavor – from author to publicity manager – feels like a bus rolling down a hill where no one can locate the brakes.

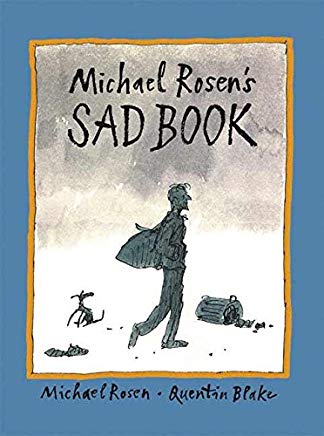

“This is me being sad,” begins Rosen, next to a strenuously smiling portrait by the iconic Quentin Blake (whom you may recognize from his illustrations accompanying most of the Roald Dahl catalogue; the deceased, seen in flashbacks, bears an admittedly disorienting resemblance to Danny, the Champion of the World). Of course this is the face he puts on for people to talk to. And the stuff that he does in his privacy – shouting in the shower, banging a spoon on the table, puffing and whoophing his cheeks – are seemingly as strange and mysterious to Rosen as to anyone reading. Arbitrary even. Deranged?

In all of this wild careening is something, I think, which is truer about the helplessness of grieving than just about anything I’ve read, and certainly in the children’s department, where death arrives often so shrouded in the magnificent consolations of nature – of parting clouds and falling leaves and painterly sunsets – that children might be forgiven for wondering if the blessings don’t conceivably outweigh the loss. There are perils perhaps in all of this metaphorical noodling, especially when the audience is not always equipped to tell the difference. Nothing wrong with magical thinking of course – with goblins and wizards and fairies to enliven the most humdrum of narratives – but you probably want to give a quick glance around first to make sure there aren’t any actual goblins out there preparing to shatter your darling conceits.

“I’ve been trying to figure out ways of being sad that don’t hurt so much,” describes Rosen, struggling to manage the darkness that seems to descend from nowhere some days, yet here are a couple of radiant little somethings to hold onto: a chicken dinner well prepared, soccer on the tube – “gooooaaaalll!” – a crane, and a train full of people, many sad, many coping, many taking their sadness out on others. Being sad isn’t the same as being horrible, he reminds himself: it’s a start. And maybe not for everyone, and maybe not so therapeutic as we may expect from such books, though probably not half so traumatizing either. I often hear parents explain they don’t think their children are quite ready – for stories about war, or divorce, or starvation, or whatever else it is that you and I are presumably mature enough to make sense of – but we are all pretty hapless in the business of death. And dumbstruck, and alone, no matter our age or our company. This book doesn’t pretend to beat a path through that isolation, in fact the last pages find Rosen still hopelessly stuck. Curator of old memories or inventor of new ones? There’s a crossroads here, even if no one has posted any signs. Ready or not. Chances are you’ll need to pass this way again.