The Blog

Blog Entry

Truth and Consequences

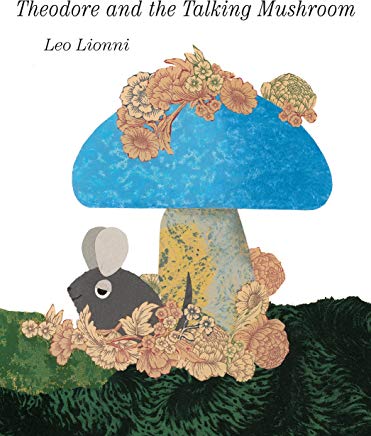

About three years ago, I picked up a brand new copy of Leo Lionni’s Theodore and the Talking Mushroom (originally published in 1971) from my local Barnes & Noble (now a Century 21), as much for how strange it appeared to me then, as the name of my son in its title. It was his birthday. The strangeness seemed a bygone sort of thing. Once in while we still stumble across it on our bookshelves here, raising an eyebrow maybe, giving it a curious flutter, and though I’m pretty sure now this represented an impulsive purchase which we have not justified since, perhaps it is anyway the sort of cultural oddity which stands even the remotest chance of fascinating – or perplexing or repelling – my children’s children, and perhaps this is not a small thing.

Because the future looks depressingly like the present when an inventory as vast as Barnes and Noble’s is not presumed to contain at least a couple of genuine head-scratchers, and yet these have lately become so rare as to appear like the last, disgruntled act of an employee so far down the supply chain that nobody remembers what she looked like. Really, how many elves does it take to focus test this genre, I wonder? If you’re not going to take any chances here at the beginning of a child’s literary experience, then you may as well turn out the lights.

In truth, this fleeting reintroduction of Theodore to the mainstream appeared to coincide with the tenth anniversary of Lionni’s death, and was probably part of some bigger roll-out where I wasn’t looking (Pezzetino Lego models? Swimmy in IMAX 3D?) so maybe it wasn’t as risky as all that. A couple of irate bloggers versus swelling brand awareness? I’m sure somebody did the math.

“This book is not appropriate for young children,” writes someone who describes herself as an early invention specialist, speech pathologist, parent and grandparent in Amazon’s customer reviews, and she’s not alone. “I am disgusted with this book [and] I am thankful I had the book shipped to me rather than directly to my granddaughter. I will be returning the book and demanding a refund.”

Anyway, here’s the deal: Theodore lives in the stump of an oak tree with three friends – a lizard, a frog and a turtle – who look like they have been trimmed from the upholstery in Lionni’s 1960’s family room. Theodore himself looks like a piece of the stuffing – the artist has used this sort of mouse before, notably in Frederick about a layabout poet – so part of the fuss about where this ends up is possibly due to our cuddly preconceptions. While each of his friends possesses a putatively magical power, all Theodore can do is run, which he does from falling leaves (mistaking them for owls) and for numerous other reasons which do not regularly meet the threshold of heroism.

One day Theodore’s running takes him to the edge of the forest where he finds shelter under an amazing blue mushroom you will not be forgetting any time soon, even if you do end up returning this book for a refund. Because it looks like the crowning, unthinkable appetizer on somebody’s Japanese tasting menu, and because it talks, or at least makes an inscrutable quirping sound which Theodore nevertheless interprets for his friends – “that the mouse should be venerated above all other animals” – and is forthwith elevated to the status of a king.

What’s a little surprising, or disturbing, or “disgusting” depending on your perspective, isn’t his friends’ reaction – “Liar! Faker! Fraud!” – when they discover an entire field of similarly quirping mushrooms across a faraway ridge; no, what finally makes this book so very different than most everything else you have ever read on this subject for children is the echoing lack of forgiveness at the end; Lionni doesn’t even give it a chance. It’s as though the artist himself were only just arriving at this quirpy cerulean vista, and could not bring himself to betray its essential weirdness with a cliché.

Theodore scampers away in humiliation. He’s never going back. The future may be bleak, or it may just be different; I can think of worse. Like imagine living in world where you know exactly what’s going to happen before it does. Now imagine reading about it.