The Blog

Blog Entry

The Passion of the Mice

In recently intending to assemble a category called Ooh La La, I was struck by how few picture books even begin to address the romantic condition. Not just marriage and commitment, with everything those imply (William Steig, for one, features a besotted dentist and his wife in Doctor De Soto Goes to Africa), but the sort of achy and irrational fixations which hobbies, or distance, or therapy, or massive doses of alcohol are unlikely to resolve.

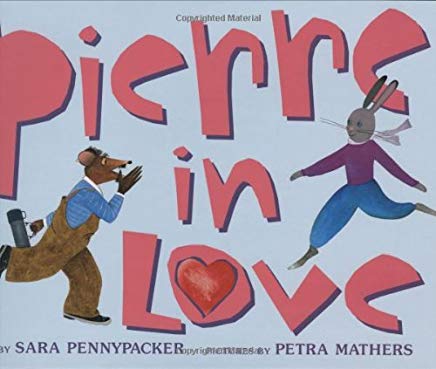

The auspiciously titled Pierre in Love does go boldly venturing through this landscape, but it came and went in a fluttering heartbeat, in case you missed it; so much for boldly venturing. I don’t know why the prohibition in this industry. (Is it prudishness? Movies don’t seem to be cowering. And last I looked, poor lovesick Justin Bieber was being marketed to five-year-olds.) Still, I think they’re squandering some pretty compelling character motivations, for starters. The eponymous Pierre is an ordinary fisherman (well, a fisher-mouse, perhaps descended from Doctor De Soto, or Steig’s Amos of Amos & Boris) with plum-colored shadows beneath his eyes, who stares into space for long hours, and hears the name of his beloved in words as unrelated as “aspirin” and “bathroom.” Indeed, everything reminds him of Catherine: sunrises, sunsets, empty potato chip bags.

Pierre’s a fine mess. His senses are heightened. And so, from the start, are our own. Look - is that a hoop earring he’s rakishly wearing? A goatee? Notice the barely nibbled sandwich set aside. Letters begun and discarded. Now also behold the spectacular luster of the ocean when Pierre is out fishing, the haunting, diaphanous daydreams skipping across his path. Or savor (as he does) the rosy, unbroken seashell at the bottom of his net. The blue scales of a bass. Witness the radiant little fishing village where Pierre returns every evening in his boat – the Cavalero of all names!

As for Catherine, she’s a bunny, round-faced and less interesting on the surface, but some kind of a multi-disciplinary artist evidently, teaching children’s dance and painting landscapes through her window, and generally practicing her pliés and grand jétés where Pierre can see them.

Pierre wraps the shell in a ribbon, then (after trying on everything in his closet, and styling his mustache with squid ink) makes an anonymous delivery at Catherine’s front door. Next: wild roses, a heart-shaped wreath of sea grass, and a dozen oysters in a bucket full of ice – all of this while envisioning baroque rescue fantasies involving a shark. When finally he summons the courage to declare himself, alas, dear Catherine has promised herself to someone else. Imagine Pierre:

“He ran to his cottage and wept like a broken wave.”

Yet a funny thing follows the hyperbole, and I think it’s as true and instructive about our unfathomable passions as all of Pierre’s mooning and fits: he survives. Yes, all of a sudden he even sees clearly for the first time in months, sunlight sparkling like diamonds, the fish “practically flinging themselves into his nets.”

“I’m as happy as a clam on the lam!” he sings to himself the next day, and I believed it. We pick ourselves up. The snub, it turns out, was one of those Shakespearian misunderstandings that never make any sense, still this book has already earned our affections by then, even if it takes a little longer for Pierre to win over Catherine’s. The ending is a sophisticated thing, but I think it’s not too sophisticated for children to comprehend. The fever – it passes. And if there is ever any trauma in all of the wanting and missing and losing, it is finally nothing compared to the gnawing uncertainty of never having given yourself a chance.