The Blog

Blog Entry

The Ancient Common Sense of Things

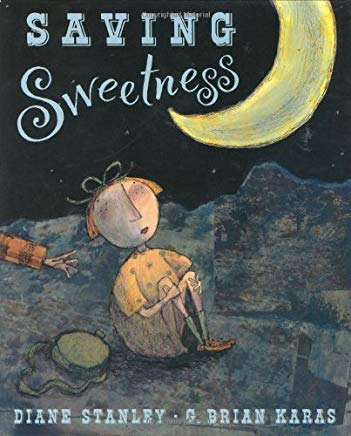

My heart has always jumped a little happening upon the unmistakable artwork of G. Brian Karas where I wasn’t expecting it. Who can say why certain illustrators affect you the way they do? Part of this is history, I suppose: sometime back when I was trying to figure out what came next after board books, Karas’s mischievous Saving Sweetness (with deadpan text by Diane Stanley) appeared to me suddenly in the middle of what was threatening to become an aimless, earnest slog, then Bebe’s Bad Dream (paranoid, hilarious), Home on the Bayou (stubborn and soulful) and many, jumpy other consolations – unlikely as they all were unalike. Ten Little Mummies (with Philip Yates) was even a pretty fun book about counting, if you can believe it.

These worked for twelve years, and two children, but mostly (maybe fatefully) for me. All of a sudden I could see clearly how a story should remain comical, mysterious, even poignant through multiple visits without straining (as movies increasingly insist) toward entirely separate levels of understanding. Which seems to me now a bargain this artist has struck with perspective, his children and aliens and alligators and sometimes even honest-to-goodness grown-ups occupying just the right amounts of canvas, between flora and fauna, over walls and through windows, zooming in and out of landscapes that do not depend for their gravity on the stories we tell about them – but maybe the other way around.

Not to try and pretend at any authority on such things, still I would imagine it’s precisely this sort of modesty which has enabled Karas’s collaborations with so many very different writers – Linda Rymill, Jane Cutler, Cari Best and Susan Orlean to name some more – none of them more fitting, or more unlikely, than Kobayashi Issa, who’s been dead for 184 years.

Their Today and Today is related in a series of seasonal haikus, which, I know – haiku? Chances are many of us remember that middle school unit, though now I think about it, you probably couldn’t have picked a more addled, less auspicious time to try and introduce the form. Anyway, don’t worry: nobody’s counting any syllables here. Instead, these are simply eighteen indelible snapshots from what is plainly - but never oppressively - the final calendar year of one grandfather’s life. Here are green shadows, a kite entangled in a gnarled tree, insects in a screen window, a small boat drifting in the tide from a hose. Here is the first snow: “The field wren, searching here, there, everywhere – has she lost something?” Here is a chair, suddenly empty by the side of the lawn.

As Karas makes clear in the preface, the life of this poet “was not an easy or a happy one,” full of death, it turns out (of his mother, when Issa was still very young, then three children of his own), a slave-driving stepmother, legal troubles, and finally a fire which swept away his house and belongings, leaving Issa to live out the last of his months in a store house, keeping company with fleas.

And I don’t know if all of his scribbling was finally a comfort to him, or a hedge against manual labor, yet it’s a timely reminder from all these miles and generations and translations away. My own days are pretty easy, I know, though I cannot shake the suspicion they aren’t as memorable as they might be, between all of the stuff that gets compulsively crammed into them, and the stuff that leaks into tomorrow. Even now, with soccer practice running a little late, a perfect summer evening descending across the city, giant, swishing oak trees overhead, a twenty-seven or twenty-eight minute bike ride awaiting us (depending if we can make the light on Second Avenue), a dog who still needs walking, pasta or pizza (or pasta and pizza) to set the timer for, messages blinking, spam to delete, a sentence to finish, a pencil to sharpen – wait, am I losing something here?