The Blog

Blog Entry

Strange Days

“I was born very young in a very old world,” conceded the musician and certified basket-case Erik Satie, but that was hardly the end of his contradictions. In M.T. Anderson’s telling, this tortured artist does plenty of torturing himself. Here is an often funny, always believable, and finally hopeful reflection on the personal deficiencies that sometimes come hitched – be they horses or carts – to makers of extraordinary art.

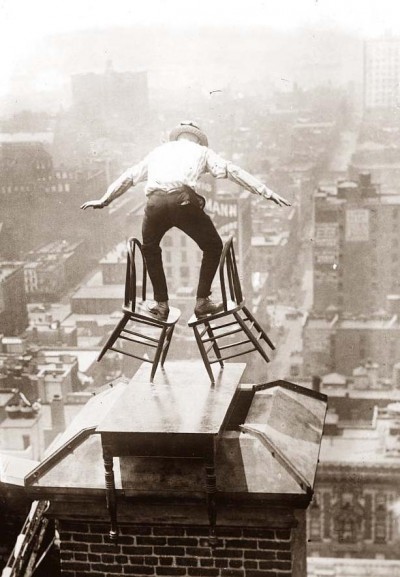

Anderson does not dwell on too many of the usual suspects (booze for one; Satie ended up dying of a broken liver in real life), but rather insists on surprising us with the sorts of scraps and significant fractions which add up to the average unknowable man. This is hardly incidental to his work: “When will people get out of the habit of explaining everything?” he pleaded across the sheet music for a ballet he named, presciently, “Cancelled.” The performance included a camel leading a funeral procession, a cannon shot into the audience, plus some of the usual xylophones, typewriters, sirens, happiness, sadness, darkness and light, kick lines and chants, all folded together and clashing and bewildering. Critics hated him. To one he composed this rebuttal:

“Sir, dear friend. You are not only a butt, but a butt without music.”

Which probably sounds more dashing in French. There was nothing dashing, however, about cuckolding a wealthy young lawyer (okay, maybe a little dashing), then throwing the object of their dueling affections out the window. Nothing probably endearing (without hindsight) about a guy who was equally aggrieved when you liked his music or you made fun of it. Who lived for years behind windows covered with newspapers, and probably hissed at small children come to have a peek.

Yet this, like any compelling biography, has a sympathetic middle between the rancor and almost-acceptance. Somewhere around the changing of the centuries, this underdeveloped man decides to actually return to the rules and the rigors of school – and he listens – after twenty years away. He doesn’t go on to become a banker or anything, but he dresses like one at least, and takes baths, and poignantly acknowledges that something had always been missing, even if he cannot make out what that was. Is this peace?

Well, it isn’t surrender. Twelve years later he’s back at it – a little more successful in his final liver-busting decade, if still blessedly misunderstood.

I had a look around on iTunes recently, expecting, maybe even hoping, to find something desperately inaccessible to prove a point, but I couldn’t, and I can’t. This is partly because I do know how to talk about music (“When will people get out of the habit…?”) but also because what I found seemed not very different from a soundtrack you’d hear accompanying something French and melodramatic – still nothing to jangle the nerves. Satie – soothing? Yeah, maybe. His music is these days apparently used to sell products on television (please, let’s try not to imagine what), but we would do well to also remember he composed a piece that took eighteen hours to properly perform.

The oddball lives on – albeit in smaller, more picturesque pieces. Published in 2003, then seemingly abandoned to the whims and fickle attentions of independent sellers, here is a book that remains true to the inspiration of a man who did not appear to derive very many consolations from an audience which had yet to be born.