The Blog

Blog Entry

Spring Back

I don’t remember a brighter or more brimming-full spring, though it is possible every year that’s my impression. Whether this is owing to the runaway depths of my personal winters, or some fortuitous recent merging of precipitation and sunshine, the forsythia where I live appeared suddenly more dazzling a couple of weeks ago than I remembered it, the cherry blossoms more pillowy, and the lilacs seem poised to overwhelm. The other day I even saw a raccoon flopping headfirst out of his tree like he had forgotten to get his air conditioner serviced. Hurry! It’s going to be summer before we know it! Maybe the little fellow was rabid. Either way, with the ground about to turn crunchy underneath me, and the publishing industry packing up for the Hamptons, I felt all of a sudden possessed by what I might have been missing these last couple of weeks in the bookstore – where there was finally nothing fresher than stories I had heard before.

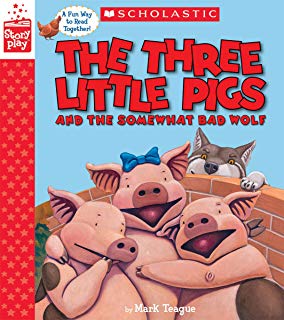

Or kind of. Just when you think you’ve read every possible variation of The Three Little Pigs, along comes an only Somewhat Bad Wolf in Mark Teague’s knowing, nuanced and surprisingly nutritional fable for our times. Here it isn’t the pigs’ mother who sends them arbitrarily packing, but a family of farmers presumably squashed by Big Agro, who pay off the pigs for good work, and eagerly retire to Florida. That two of those pigs turn out to be slackers will surprise no one perhaps, but that their fecklessness should firstly consist of a weakness for potato chips and “sody-pop” struck me teachable and laughable in just the right amounts. The most industrious among them meanwhile plants a vegetable garden to go with her red brick homestead, and the wolf only resorts to all of his huffing and puffing after first being turned away from a donut shop, a hot dog stand and a pizza parlor.

“I was so hungry I could not think straight,” he avows after passing out on a manicured front lawn. Hey Wolf, I feel you, man – and so do the pigs. Every child should learn the word “somewhat” before they’re five, which is not incidentally the outer range of Amazon’s recommended age for this book, which is not unpredictably tone-deaf. Really, when are we ever too old to learn a little moderation?

As a newly minted parent and designated early morning reader, I was always on the lookout for the sort of classically illustrated, straightforwardly narrated selection of nursery tales that you could practically recite in your sleep – then sometimes actually in your sleep. This literary holy grail which I never exactly succeeded in locating, should meanwhile mistily replicate the simple verities of my own implausible childhood, even if many of the stories make no sense to me now. What mattered to me then was only its certainty, with the day looming chaotically beyond sunrise. You should be able to throw it in a bag, refer back in a spiritual emergency.

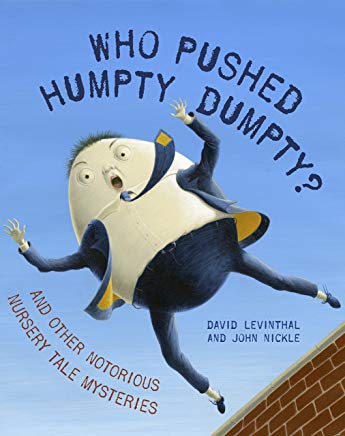

Whether Who Pushed Humpty Dumpty? And Other Notorious Nursery Tale Mysteries should hasten such an emergency or merely acknowledge it will probably depend on one’s age (here again, the authorities recommend a forbiddingly narrow window) and native skepticism and whether you are living in a cult. Maybe not for everyone then, but for the questioning mind I found this weirdly, and hilariously, reassuring.

“There are eight million stories in the forest,” begins Binky – a toad, a detective and committed empiricist – firstly answering a case of breaking and entering from three understandably shaken bears. Goldilocks gets what’s coming. It may surprise you how finally satisfying this proves.

There’s also a disappeared witch to account for here, and two photogenic kids with an alibi, a beauty contest where the fix is in, and the title story in which a pig is tellingly observed flipping omelets at a breakfast stand. Turns out all he wanted to do was play in Humpty Dumpty’s band. A crime of passion then. Add to the mayhem one crash, a dead giant, a likely story. “Okay Goldie,” says the toad to the goose who resumes her rightful place as a storyteller in these pages. “Let’s get down to the station house. Lay a couple of golden eggs along the way. We’re going to need proof.”

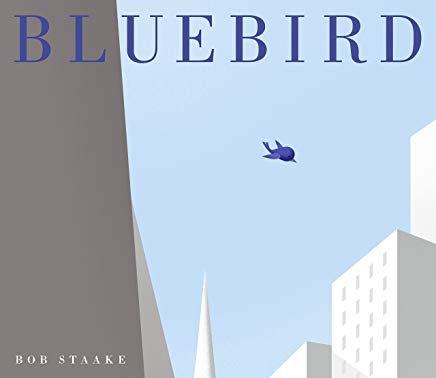

If this all sounds suspiciously like something you would read for your own selfish benefit, well then, Bob Staake’s Bluebird might not require your services at all. For that reason alone, books without words have never been at the top of my personal wish list (What are you even supposed to do while you’re turning the pages. Point? Mutter questions? Whisper hmmm?) and yet there are some plenty riveting stories buried behind pictures, especially when we manage to remove ourselves from their margins. This book looks pretty transparently inspired by “The Red Balloon” – the movie, not the book, where the text always seemed a little extraneous anyway – though I think it’s a story whose updating was overdue. 1950s Paris can seem so heartless and almost medieval as to require at least a PG rating, but there’s nothing remotely menacing about Staake’s gray-and-white landscapes, in fact this is a city, like the boy who inhabits it, which only asks some brush of animation.

Everything’s here: the trees for climbing, the cookies for sharing, the boat pond for imagining – there’s even a bookstore called the Steadfast Independent, if you are looking closely. All of this strikes me as especially poetic in an age when we are increasingly turning to our fingers for social interaction. The bird of the title is really more purple than blue, possibly to avoid being mistaken for a Twitter icon, and makes its introduction during a typically dreary day at school – two truculent bullies at an adjacent table barely rate one upturned eye. We’ll cross their paths again, sure enough, though cruelty is never really the obstacle here, only indifference, and even the bullies are finally roused to contrition. I can’t say with any certainty what all of the different colored birds are about in the end, but they are an eyeful, one question becoming many, a conversation ever likelier to begin.