The Blog

Blog Entry

Speak For the Trees

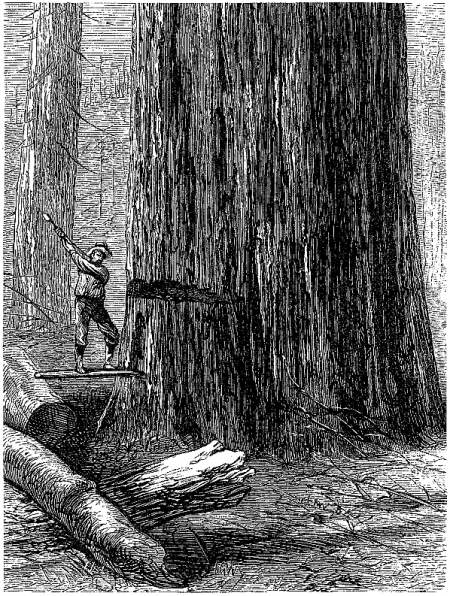

I am, admittedly, a sucker for books about trees, not least for the irony inherent in singing the praises of something that needed to get chopped down for you to even exist. It’s like erecting a billboard to advertise a scenic view – but not this scenic view! Pulp these days comes from aspen and pine and spruce and birch and eucalyptus, but regardless of pedigree, books about trees carry some burden – call it conscience? – to prove at least as valuable as the trunks and branches they replaced, the buds and leaves and cones and rustling shadows and clockwork metamorphoses and places to lean against and climb and hide from winters and predators and each other. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe books about trees are just as often shameless as books about furry cartoon animals and fairy tale princesses, still show me a book about a tree, and I am generally hopeful about the author’s ambitions, whatever the opening premise. I don’t care if the tree runs away with the circus, I’ll give it a couple of pages.

Because if a tree runs away with the circus, it probably had a pretty good reason. It takes a lot for a tree to finally lose its composure. In Karen Gray Ruelle’s The Tree, for example, it takes two wars, two epidemics (one human, one botanic), depressions, fires and parades – it takes a considerable cross-section of American history to outlast the great elm that finally stopped growing three years ago in Madison Square Park in New York City. Yet there it still stands, a massive, indomitable husk, mercifully unlabeled, and every bit as impressive as all of the historically significant architecture which surrounds it and draws tourists from thousands of miles away. There’s a Shake Shack at twenty paces, lines around the block, and oceans of natives on lunch breaks, yakking too loudly into their Bluetooth attachments, or to themselves – everywhere such babble and otherwise spinning-of-wheels to make you wonder if maybe the elm didn’t pick a pretty good time to stop witnessing history.

The oldest tree in the world dates to about 4700 years ago – almost three thousand years before Christ! goes the saying - though of course trees don’t give a fig about Christ, or me, or you, at least until we start rooting around in their rings, and pulling off their branches for our mantels, which is why the actual location of the oldest remains a mystery except to Dick Cheney and a couple of wily botanists – which I think is kind of cool. Because, really, we have options. There are trees you can drive your car through in California if you want, and help to solve a budget crisis, and there are possibly trees in your very own yard which took root from an acorn discarded by some idiot squirrel – now million-times a grandfather – and this nut became a sprout, and it jostled with rocks, and was randomly spared – a foot, a blight, a foundation – and now you can climb it, and rake its leaves, and depend on its shelter.

A Tree is Nice wrote Janice May Udry, describing these and many other gifts in the simplest, inarguable terms (think about it – is anything really nicer than a tree?). We do not suffer from these reminders, particularly as adults, and particularly when we live in a city, where the very fact of an acorn even taking root can sometimes seem as unlikely and supernatural as an alien invasion.

It’s enough to make you watch your step. The fact of a tree dying in our midst, or in our lifetimes, can seem like a spectacularly unlucky coincidence because, I think, we take for granted the seasons it provides, the mixtures of sunshine and shadows in our photographs when we were four and twelve and forty, sisters or fathers or grandparents. Then there’s the vista behind it as well, which becomes suddenly more central, and inadequate, when that elm, that spruce, that oak has disappeared. It’s like waking up one day and seeing things in a different language. Like throwing away that growth chart, that yardstick, like such a thing as “inches” maybe never existed, and we are henceforth compelled to measure our evolutions with sundials, carbon isotopes, and random human impressions.

So chaos. In Our Tree Named Steve a father writes his children to inform them and try to console them (though it didn’t do me any good) about the fate of a tree bearing the name of a mispronunciation from many years before:

“... in a world filled with strangers, peace comes with having things you can count on and a safe place to return to after a hard day or a long trip. Which brings me to the point of this letter…”

Yeah, that about killed me. I don’t even want to think about it sometimes, but there it is, when I am up to it, and there is also Ellen’s Apple Tree about starting over, or anyway planting another yardstick, which seems to me a kind of hopefulness more particular to the identity of trees bearing fruit, where every year requires a little care, a little patience, and a special leap of faith.

There’s The Birthday Tree, by Paul Fleischman, about a tragic young family that settles on a hill with a sapling that thrives and grows and blossoms as they do, while also reflecting the perils of a larger, more treacherous, and sometimes more generous world than they can control from their little patch of it.

And there’s The Giving Tree, yes – by that wild Shel Silverstein – about which others have famously declaimed, and the rest of us have famously strong opinions, most of them thoughtful, committed and not careless in the way of leafing through a book about a tree running away with the circus. You either really like this book, or you really don’t, and the few of us who don’t have an opinion probably haven’t read it, so here goes: A boy grows up, loving and playing around a tree, carves his initials in it, carves his girlfriend’s initials, cuts off its branches to make a house, and so on, growing wartier and more selfish until nothing remains of the tree but a melancholy stump. There’s a whole lot to say on the matter (it’s a bigger, more challenging subject than I can manage while thinking of poor Steve) but I’m generally in favor of stories as concerned with the warts as the people who grow them – for this is a part of our journey – even if a tree should need to die for us to see it.