The Blog

Blog Entry

Sees the Day

That the twin towers were standing for only twenty-eight years remains surprising when you consider the fixtures they became in so many representations of New York, but it took a street performer to immediately recognize the opportunity afforded by their unprecedented arrangement – this before their construction was even complete.

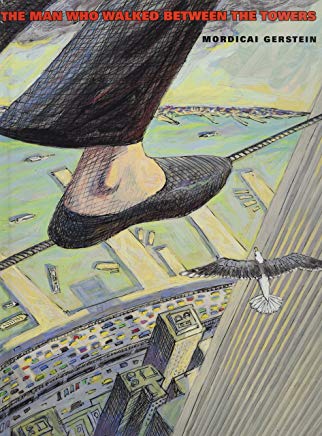

The basics of the story are a matter of historical record – Philippe Petit hung out his wire between what were then the tallest man-made structures in the world, and was promptly arrested for his impudence – but the details merit revisiting, and perhaps a little embellishing as well. In The Man Who Walked Between the Towers Mordecai Gerstein describes the wire – 440 pounds of cable actually – and a couple of Petit’s conspirators (yes, he did have help) who were almost pulled overboard in the course of their preparations. It was just before dawn when Petit climbed out there, he actually stayed for a couple of hours, and even pretended to be napping at one point, before happily surrendering to custody. Finally, he was never imprisoned, but committed to performing his community service for children, which he allegedly did not mind, except when a couple of brats went pulling at his equipment, and he almost – anticlimactically – bit it.

Still, what’s crucial to this story were the mornings Petit spent wondering over that skyline - and finally less about the towers than the shaft of wasted air between them. Certainly this is the gift, and often the curse, of inspiration – to look where no one else has thought – but then so is the urgency of seeing things through to completion in the limited time that we’re given. I am barely old enough to recall the image of that crazy Frenchman in his grubby circus V-neck, but he actually dressed up as a construction worker to win his passage to the top, something inconceivable amid the security conditions of today, or even a couple of days after it opened – days, and prohibitions, Petit surely knew were coming.

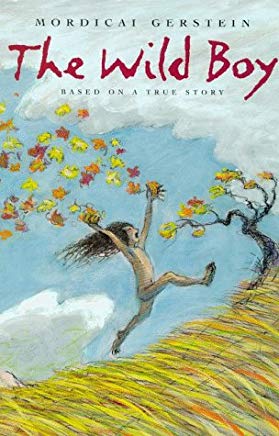

This compulsion of getting things right in the crystalline, limited moments we are offered is something like a theme in Gerstein’s work, and there is necessarily an ambiguous, even elegiac color to the end of a lot of his stories. In The Wild Boy, also based on a true account, a young doctor is palpably frustrated in his attempts to completely reintegrate a boy found naked and scrounging in the forest (“He will never learn to speak, thought the doctor sadly. He was alone in the silent woods too long.”) but his efforts, and the reactions of the boy, are the stuff of great storytelling, as credibly detailed as they are unpredictable.

We spend so much time talking and writing and reading about seizing the day, it’s a miracle there is anything left over to seize. Parenting magazines in particular are full of suggestions about how to get your kid to love books. Sometimes they’ll recommend a couple of titles, and usually they’re the ones that are recommended just about every place else. Mostly, however, much wisdom is dispensed in the area of creating a positive atmosphere, as though half of our duty should be accomplished if Martha Stewart came calling with a couple of earth-toney pillows and a little white noise. This sounds like procrastinating honestly, and it sort of misses the point. Because eventually the stories that take us back, or away, or toward better, implausible worlds owe less to what everyone is saying than to spaces we fill for ourselves.