The Blog

Blog Entry

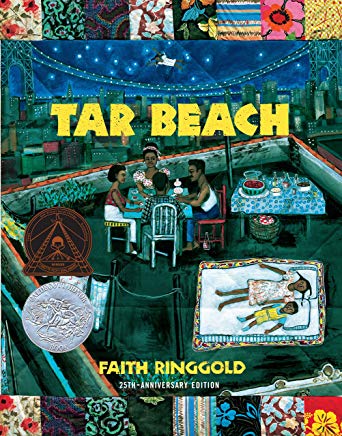

Roofs & Bridges

Faith Ringgold would not have been able to see the George Washington Bridge from her rooftop at 363 Edgecombe Avenue. This may come as a surprise to readers of her beloved Tar Beach, in which that bridge (then the world’s longest) played a significant role in one girl’s imaginings of a life that was forever personally available, even while it was being denied her father, who was often between jobs, barred from joining unions, and once upon a time participated in the hoisting of those unprecedented cables.

It’s a breathtaking metaphor on so many levels; imagine the stories you could tell around even the tiniest fractions of its magnificent bulwarks glimpsed across the thousands of tar beaches stretching eventfully through Harlem to the Hudson River.

And who would you tell them to? In fact, the site of Tar Beach was actually the rooftop of a building that was visible from Edgecombe Avenue, which isn’t as far removed as it sounds. When the six-year-old Ringgold was out there picnicking on a warm summer evening with her family and Mr. and Mrs. Honey (so named because “honey” was how they addressed you) she might have walked across four rooftops (then unimpeded by the coils of barbed wire that separate them today) and had a word with Sonny Rollins before he became one of the most influential saxophonists in history; six or seven more rooftops and she might have found Thurgood Marshall kicking back with a beer between arguing Brown v. Board of Education, or W.E.B. Du Bois taking a well-earned hiatus between writing and teaching and founding the NAACP. Then from there, if she squinted, she might have noticed Duke Ellington enjoying the company of friends and other ground-breaking musicians a couple of blocks away on St. Nicholas Avenue. Duke Ellington might have been able to see the George Washington Bridge.

“I had all these creative people living around me,” said Ringgold recently in an interview with The New York Times. “We all lived together, so it wasn’t a surprise to see these people rolling up in their limos. And that said to us, you can do this too.”

On its surfaces Edgecombe Avenue probably did not look very different in 1942 than it does today. Those streets have been spared any taller, partitioning developments, and a tree-lined promenade runs interrupted for a dozen or so blocks between a modest succession of brownstones and a park (now named for Jackie Robinson) descending steeply below.

That park seems well-trafficked – between climbing structures for toddlers and baseball diamonds, and footpaths and handball courts – though it’s hard to know if anyone is still taking advantage of the perspective afforded from five and six stories on top of the street. Maybe. Still, I hope they’re not up there on the phone, for heaven sakes, or trying to access free wireless beamed in from the continent (we are, after all, still an island) and I hope they’re not playing a game with someone in California. This is nostalgic admittedly – I’m not the first reader whose eyes have been permanently tattooed by Ringgold’s aerial views and quilted, spectacular margins – though surely there is some peril in spending so much of our lives between places, of traveling so far and so fast and so frequently, that we cannot make out when we’re flying.