The Blog

Blog Entry

Prairie Fever

As a kid I moved around a lot, and so tend to romanticize the experience of growing up and growing old around familiar landmarks and people you’ve known since you were toddlers. Add to that fantasy the occasional frustrations and disappointments of living in a very large city (where my children have, in fact, known some of their friends since they were toddlers), and my reveries start to extend to the putative pleasures of small town life such as they are depicted in Bonnie and Arthur Geisert’s version of a classic Prairie Town where everyone knows your name, where the townspeople’s social schedules are more often than not dependent on seasonal imperatives like planting and harvesting, and where in the most literal sense, “life is affected by the weather. A town’s business depends on the farmer’s good fortune. Rain can insure a good crop. A hailstorm, drought, or tornado can destroy it.”

And yet: “On beautiful days the whole town is the children’s playground.”

In Desert Town, also by those meticulous Geiserts, the temperature is often so oppressive that basketball games can only happen at night, in blue jeans, against the side of a cafe, with all of the ramshackle joy of a special occasion. And – look! – there’s a couple kissing in the shadows, and maybe everybody’s talking about it the next morning, and maybe that’s not so bad.

Maybe it is. Five pages later, also in those shadows, the young man appears to be proposing, down on one knee, and we are tempted to imagine all that happened in between. This isn’t Hallmark territory in other words. If each of these books represents a tribute to the simplicity of small town life, then it’s not without a touch of elegiac sadness. Back on the prairie, the circus blows through town once a year, and you wonder how many youngsters aren’t hanging onto its tailgates on the way out. In these, and the Geisert’s Mountain Town also, people seem to spend a lot of time shoveling themselves out from under snowstorms, the respective economies appear to be teetering on the edge of viability, indeed the eponymous mountain town is actually a relic from the age before all of the gold and the silver ran out.

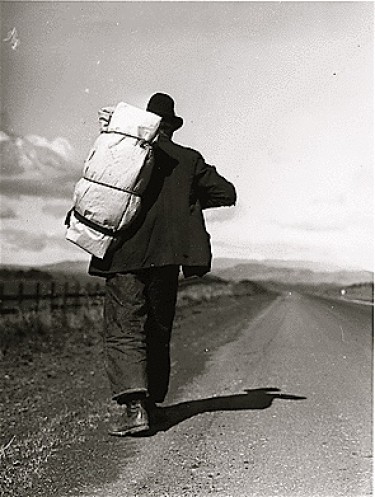

My fingers get numb in cold weather, I hate going to church, am wary of community-sponsored spectaculars, and don’t like people in my business unless I specifically invited them. I’m not patient, not handy, and I don’t want to live in a small town, still I am comforted and even a little ecstatic to know that there are generations of people who still do, and remain committed to building and slowly evolving rather than interminably chasing the next, better thing. If there is a lesson to be learned from their happiness, then it is fighting some pretty stiff headwinds from all of the usual places. Following your dream looks great on television, in movies, in children’s books even, yet maybe we benefit from this caveat also, that the biggest and often most original kind of dreaming doesn’t necessarily come announced by a change of location.

From Dawn till Dusk, by Natalie Kinsey-Warnock, tells of a girl debating her brothers over the benefits and likelihoods of their remaining in Vermont through the long, bitter winters to come, indeed they even wonder about their Scottish ancestors: “Why’d they ever move here?”

Because they found stuff – if they were lucky – to look forward to, whether pickles or doughnuts or mud pies or ski jumping off the roof of their barn. Or stumbling upon “old cellar holes and cemeteries with the names of [their] ancestors carved in the stone.” And holidays: Christmas, the Fourth of July. Holidays always sound like they earned them in the country.

Still, I like where I am. In a book of that title, by Jessica Harper, a six year old boy is rightfully alarmed by the sudden appearance of “really big men, eight feet tall, or nine or ten” come to pack up his life into boxes and move the family to a place called Little Rock.

“Take your truck,” thinks the boy, “and take your Trouble and move somebody else,” which pretty much sums up how I feel about moving these days. I’ve got the place that I buy my baguettes, and the place I get my haircut, plus I’ve got all of my stuff: the papers and tchotchkes and junk we’d probably throw away before we paid someone to move it, the couch that probably wouldn’t look good anywhere else, and the paintings that might or might not, and the photographs that are likely to betray any real memories of where I actually grew up, even if I was already well into my thirties when that happened.

And I have these reminders when I am occasionally compelled toward the busier crossroads of my adopted hometown, through hordes of tourists aiming their cameras in the usual trajectories, somewhere suspended between awe and disappointment, between the bother of arrival and the bother of remaining – because maybe there’s a break-dancer around the corner, a peepshow, a celebrity, a toilet – I live right at the edge of this lit-up, amazing example of all the stuff you that you miss when you go looking in the likeliest places.