The Blog

Blog Entry

Ne’er-Do-Well

Where have you gone, codswallop? Granted, there are nowadays snappier ways to communicate one’s impatience, still every once in a while I heave a little sigh for the old-school ostentation of “balderdash” and “woebegone” and “tomfoolery,” then sometimes I even catch myself directing whole stories toward those rhetorical mountaintops just to remind myself they still exist.

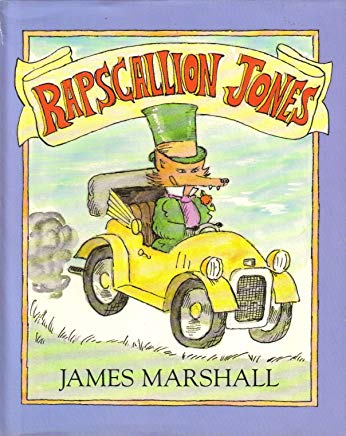

The great James Marshall takes an opposite approach – probably less strenuous, possibly instructive – defining his fox before offering any evidence, and yet the story of Rapscallion Jones is finally so brimming with shiftlessness and double-dealing that no other word will suddenly do. Scalawag? Flâneur? No, of course not:

Rapscallion.

Parents please note: the risk of your child ever mistaking this fraudster for a role model seems well worth the possibility of their using a word like rapscallion in polite conversation. I’m not sure this is a great book, or even coherent some of the time, but there’s poetry here, a dizzying and ephemeral thing. The Mr. Jones of the title is a layabout boarder not keeping up with the rent, who nevertheless cannot conceive of getting a job. Maybe he could marry a rich widow? Yellowing teeth and an overall decline in pizzazz seem to argue against that.

“I have decided to become a writer,” he announces one morning at breakfast to his startled fellow boarders, then quickly hits a snag when all of his latent talent, many strong cups of tea and a whole box of paper clips mysteriously do not add up to story.

Not for Jones, the long, dark night of the literary soul, and pretty soon he’s out on the streets regaling the local ne’er-do-wells with a tale of two crocodiles that may or may not have happened, involving gobbled chocolate kisses, medical malfeasance, and a sack of dollar bills burning a hole in the freezer. You haven’t understood the maximum potential of picture books until you have witnessed a skulk of good-for-nothing foxes guffawing through cigarette smoke at the brazen bamboozle of reptilian bourgeoisie.

There’s also Mama Joe, a bulldog of a landlady chomping a cigar, a death bed scene, a doctor who probably does not just happen to be a crocodile, a midnight call to a priest. A lot of silliness, in short, which you are free to invest with deeper meaning, and metaphysical layers, or merrily follow along. Jones takes up painting in the end, a natural for anyone blessed with unruly imagination and a jaunty French beret, who nevertheless discovers himself a victim to the unquenchable promise of words.