The Blog

Blog Entry

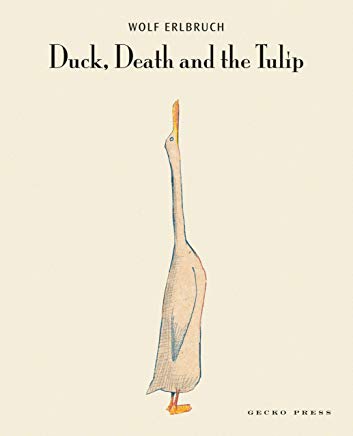

My, What a Big Skull You Have

I’m not quite sure of the intended audience for Duck, Death and the Tulip, which is only one of the reasons I snapped this bad boy up. Actually I was a little stunned to happen upon it a few weeks ago at the New-and-Used bookstore in my zip code, mentioned it here in passing, and was afterward suddenly seized by the urgency of owning this recent import from Germany. When I returned, and it wasn’t there, I even panicked a little that the American book-buying masses had probably discovered it, and caught the fever, and hoarded copies, and I’d had my chance and missed it. Curses! Either that or it was deported. Turns out, though, my precious had only been relocated to the Death and Dying section alongside titles about earnest looking bunnies gazing up into the heavens. It’s not a great section - not vexing, or awesome, or any way mysterious, which this book, at a minimum, is.

Still, now that I own it and nobody can take it away for me, or charge me late fees, or price it at two hundred dollars on Amazon – now that I own it for not quite the cost of enduring “Titanic” again in three dimensions, I see how this is a book that will require some poking and prodding and many times revisiting before I am ever able to arrive at any conclusions. Like, for example: “Elegant, straightforward and, above all, life affirming.” Pity the poor intern charged with that dust cover copy.

I’ve passed it around. People don’t like the look of Death is the reaction I get. I wonder if this is because a skull in a housecoat is at odds with Death’s otherwise thoughtful, kindhearted and, um, elegant demeanor here, or because we have generally been conditioned to associate such appearances in picture books with kooky Halloween fables. Either way, Death doesn’t make it to the cover, only duck, apparently perusing the heavens, for the first and only time in this book.

Or maybe he’s looking up into a tree, just one of the places they visit together after meeting cute (“What are you up to, creeping along behind me?” “Good,” said Death, “you finally noticed me. I am Death.”), and also where this quirky meditation began to feel like more than the remainder of what was conceivably lost in translation. Like the eponymous Tulip itself, which nobody ever speaks of, still there it is, at the beginning and the end.

But the tree. For reasons that Wolf Erlbruch doesn’t waste a lot of time explaining, Duck and Death decide to go climbing. There, amid branches and berries, they peer down onto a pond where they have just indulged in an equally spontaneous dip, then a nap, Duck draping her wings across Death because (little-known fact) Death tends to get the chills.

“So still. And so lonely,” thinks Duck about the pond. “That’s what it will be like when I’m dead.”

“When you’re dead, the pond will be gone too - at least for you….”

“Let’s climb down,” Duck pleaded after a bit. “You can start having strange thoughts in trees.”

But is this really too strange - or disturbing - a thought for your average five- or six- or seven-year old American reader? That’s your call, especially if you are a parent of the single average child in each of those age groups, or you are a mind reader, or you have written a book on the subject. All of us construct our ivory towers at different heights, in different landscapes, with different broadband capabilities, still a river runs through them, sometimes spilling onto its banks or shrinking out of view, delivering the good, the bad, the halfway recognizable before we know enough to say goodbye.