The Blog

Blog Entry

Must Pay the Rent

How people spend their money – and when, and where, at what perils – has always been a source of inexhaustible fascination for this observer. I know families who appear to be scraping the bottom – in how they dress, and where they live, and how they complain about their material circumstances – then all of a sudden they are pulling up in a fully accessorized luxury automobile. I know people who work civil service jobs and think nothing of dropping three or four bills on getting their hair done, or Pilates, or piano lessons for their kids. I know people living in two-million dollar apartments who appear to wear suits that have followed them through the decades from college. Such people are often willing to travel an extra hour to secure a bargain on paper towels, then fret about a penny or two more for each gallon of gasoline.

This says a lot about the lives of those neighbors to which we are otherwise not granted transparency, still just as invaluable from all of this nosing and comparing are some of the doubts we are willing to admit about ourselves. Are we reckless, impulsive, or are we taking the longer view when we shell out for that Caribbean vacation every year, or send our children to private schools?

That we do not very openly explain those priorities is presumably in the interests of insulating our sensitive young ones from tough, or unpopular, positions, though I think there are equal perils from pretending that everything is sort of free. Now more than ever – as the news from our televisions and our neighborhoods is so loud with the sound of the other shoe dropping: of payments coming due and investments imploding. When money is so clearly something we can no longer conjure out of thin air.

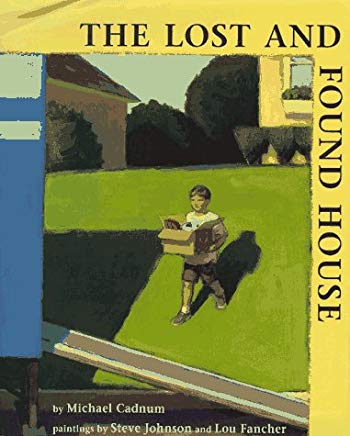

To read children’s books – at least the ones relying on pictures to help tell their stories – is to enter a world that seems oblivious to such consequences. Like one of those sitcoms, for example, where everyone lives in a very big apartment and works cool-sounding invisible jobs, and fusses uproariously about bills bills bills, and babies never cry, and if they do, they sound like cats.

Okay, maybe not that funny, but still. There are some pretty great books – full of heartache and optimism – on the subject of moving, but why did the families in these stories up and relocate except to probably follow their fortunes? Cheaper rents. Better jobs. Monsters weren’t chasing them out of there.

Which is conceivably what we do with the topic of money – we make it bigger, scarier, monstrous – when we do not address it directly. There are so many ways, and they do not need to result in a sense of helplessness, or whatever else we’re so worried about passing along to our kids. I’d like to see somebody write a really good book about a lemonade stand, for example, or otherwise under-age entrepreneurs, but for that you may need to wait till chapter books at this point. (John Fitzgerald’s The Great Brain comes to mind.)

What about tales from the Depression: they don’t only need to be depressing, do they? Kate Lied has written a very accessible book called Potato (that’s right) about one family on the move between Iowa, Idaho, Hawaii. A father loses his job at a service station, a family loses its house to the bank, but they find their feet again picking potatoes for two weeks: with the farmer’s permission, the ones that they pick after hours they are allowed to take with them to begin a new life. This story arrives courtesy of National Geographic, some urgency muted in the telling (by somebody’s grandmother who got out alive), still it’s no less timely for being nostalgic.

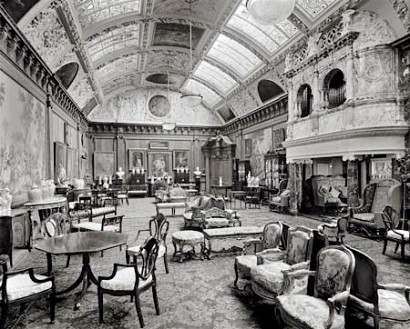

From a cover designed to resemble burlap to one in the likeness of a green dollar bill: probably one of the most elucidating (and, not incidentally, entertaining) books on the subject of money concerns a family who could not be less concerned about money at all – where it comes from, and where it goes – at least till the jelly runs out. In the middle of a gala event no less, whereupon the eponymous Hubert Horatio Bartle Bobton-Trent is sprung from his purebred complacence, rustling up some cheese on toast, pawning a hideous lamp, entering his parents in board game contests, and organizing tours of the estate. I’d like to see Merchant Ivory have a crack at Hubert Horatio. The boy and his family end up moving to a serviceable tenement (at 17B Plankton Heights) where the father finds his calling as a doorman, and everybody lives intimately ever after.

You will recognize the brilliant author and illustrator of this book as Lauren Child, who seems to have run out of eye-opening things to say about Charlie and Lola, though they continue. Because, hey, it’s a business.