The Blog

Blog Entry

Lost in Bonkers

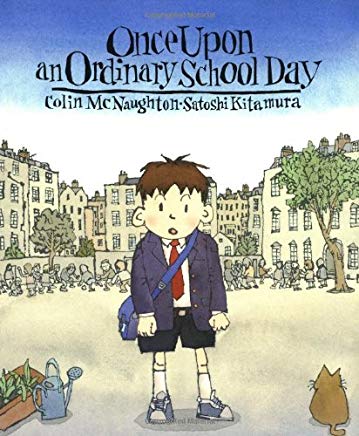

An extraordinary teacher shows up in the middle of Colin McNaughton’s and Satoshi Kitamura’s Once Upon an Ordinary School Day, though whether he is finally the sort of effective educator who has been recently, contentiously championed is for your interpretation. What’s he doing schlepping a clunky old gramophone into the classroom when there are probably standardized tests somewhere right around the corner?

“He’s bonkers,” whisper the ordinary school children. “He’s as nutty as a fruitcake,” but there’s method in his madness – enough you vaguely worry about a future when such madness has finally been abolished. Not everyone benefits from Mr. Gee’s music (“rumbling, rolling, thunderous”) or Kitamura’s paintbrush (Barry Pearson falls asleep, Pauline Crawford reads Wonder Woman, and several other students go monochromatically daydreaming about a boy with a lightning-shaped scar on his forehead).

So their loss. But society’s? Reading this book back again, I was reminded of all of the unquantifiable wonder that ends up getting left behind while we are busy accounting for Barry Pearson. Everywhere the talk these days is that we know what works, as though the challenge is simply in the implementation, but the longer you listen, the more it sounds like the only thing we really know is what doesn’t work, and that is only because we’ve passed those weary ways before.

Some of us are old enough to remember the genius of blasting down walls in the service of utopian mega-classrooms filled with a hundred or more kids moving creatively between activity stations, and in and out of supervision, then some of us remember reading about ourselves a couple of years later in Lord of the Flies. Some of us remember the reappearance of those walls. And SRA reading kits in all of their color-coded modishness – and fraying obsolescence. New math. Math without tears. Oh, the language has changed, but no one should lately feel cheated for living outside of an era of educational derring-do.

And I think most of us fondly remember someone a little like Mr. Gee, who was possibly not long for the profession, or possibly too long already, and who either way appeared to share our mistrust for the current curriculum, which possibly made him sound more dangerous than he was. We could take him or leave him of course – no pop quiz awaited that would measure our comprehension of his rambling – but in those rarest of cases we found ourselves soaring for not being tethered to a bottom line.

“He used words he didn’t fully understand, and it didn’t matter and he didn’t care,” writes McNaughton, not, in this case, about the tenured raconteur, but the student who is stirred, against all ordinary odds, to express himself on paper. “And he wrote as fast as he could but it would never be fast enough – there was too much to say….”

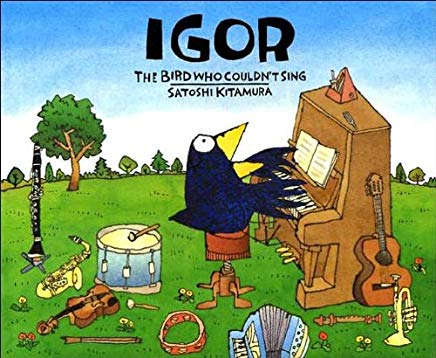

That this happens in response to a symphony is what probably attracted Kitamura, a spokesman for the transformative spirit of music since the moment the desert sky burst into bloom at the end of Igor, The Bird Who Couldn’t Sing. Indeed this story is even rescued from a certain gray-and-white tedium by his glorious panoramas – of mingling with elephants and dinosaurs, and hitching a ride on a dolphin, of witnessing the curve of the earth with the birds. “He was lost,” describes McNaughton of the school boy, “lost in the game of storytelling,” although it’s fair to also wonder if math is not a sort of game, and history, and social studies, and whether in fact there is anything worth learning that does not require a little getting lost first.