The Blog

Blog Entry

How Bizarre

Any book about being odd has, I think, the sacred obligation of being at least a little odd itself. This is especially true of the books that we read with our children, where at stake is perhaps the very definition of oddness for generations to come.

I don’t know if you can aspire to oddness any more than you can call yourself crazy, and yet to hear people talk, I think both conditions have probably never been so popular. More than anything now it seems obscurity that terrifies, so we pile on the quirks, but if I’m odd and you’re craaaazy, then which of us can even be trusted to tell the difference?

Show me the oddness! And it’s not enough to pose provocatively on Facebook or pierce your every cleft and bulge. I have a feeling we may have ruined this already for ourselves, but that doesn’t mean it’s too late for our kids. Or a couple of them, at least. The future may even depend upon it! Picture some biddy at the dawn of the twenty-second century, toddlers gathered around her hover-chair:

I remember odd, she is telling them. Odd was a secret. Odd was not knowing any other way.

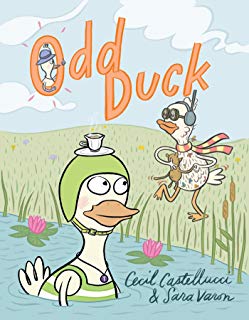

“Every night Theodora fixed herself a fine supper, gazed up at the stars, and made a wish on the first star she saw. Her wish was always the same. Theodora wished that nothing in her happy life would change,” describes Cecil Castellucci in Odd Duck, a surprisingly poignant, often hilarious meditation on otherness with brimming-full illustrations by Sara Varon. Still, I’m not sure this book would ever stop you in your tracks between most of its cornea-blistering neighbors, indeed it may even end up requiring a couple more minutes and a greater attention to detail to fully appreciate just how different from her neighbors Theodora really is.

Or it may just need regular revisiting – which makes this one of those rare and thorough stories actually worth surrendering nine or ten bucks for the privilege. Its creators certainly put the work in. Yes, there are chapters, dear flibbertigibbet, but they are short: the first, an affectionate rendering of Theodora’s average day – grocery shopping on her bicycle, and checking out rarely-opened books from the library (“Duck Space Stories”) and swimming around the pond behind her house with a cup of rose hip tea balanced on her head. For good posture. Hmmm.

In Chapter 2 it is the arrival of Chad, a new neighbor, that proves impossible to put down – simply because we cannot get to the bottom of him, between his conceptual sculptures and “violent dancing” and not-well-oiled plumage dyed in tufted, lurid colors. He has dreadful manners, drinks racy cocktails, never stops hammering on things, and even neglects to fly south for the winter – oh, for heaven’s sake!

But he knows stars, more than Theodora has ever considered, and all it requires is that single mutual interest for Chad to seem incrementally not so odd. Still, maybe he is. Still, maybe Theodora is odder. Duck food really is pretty dry, both agree, but what is finally a greater abomination to average duckness, the artist’s lemon mayonnaise or the homebody’s mango salsa? You decide.

And what of Theodora’s “uncontrollable twitchiness” when the two have a falling out? The nervous pacing, the “general malaise.” When was the last time you heard “general malaise” in a picture book? Is this strictly for us parents?

I think not. Whatever our ages and implacable urges and mysterious moods, and whatever the words we learn to explain them, we are all surely a little odder to ourselves than we could possibly be to anyone else.