The Blog

Blog Entry

Hoots and Shadows

In our darker hours, don’t we sometimes wonder if every story has already been written? A couple of days ago I was waiting with my son in the doctor’s office, next to a potted half-dead fichus, and my son asked, Is it real? and touched the leaves, and I said, Why would anyone bother to make a fake that looked like that? And then I got to thinking how there was probably a good book to be imagined about a houseplant wasting it’s natural lifespan in such miserable circumstances, but lots of people had probably done it, with morals and spiritual uplift and many-colored ribbons along the way, and that was somehow even sadder than the plant.

Okay, my darker hours maybe, still once in a while the world looks positively aglimmer with narrative possibilities that seem scarcely more symbolic than something we saw when we were out driving. That is conceivably the genesis of House Held Up by Trees, which I suspect I am lucky to have stumbled upon only because its illustrator, Jon Klassen, has recently collected so many critical accolades for I Want My Hat Back, which I have written fondly about here, and chortled over, and many times guessed at the collective American amazement at its ending, and chortled some more, but seriously, people, let’s pull ourselves together. The bear eats the rabbit, okay? That you didn’t see this coming surely says a lot less about Klassen’s storytelling genius than the state of animal fables today, and nutty, kooky literary juries. Somehow I liked this much better before it got branded. Oh, it’s still a hoot, but can we please hold off on the Pulitzer for a second?

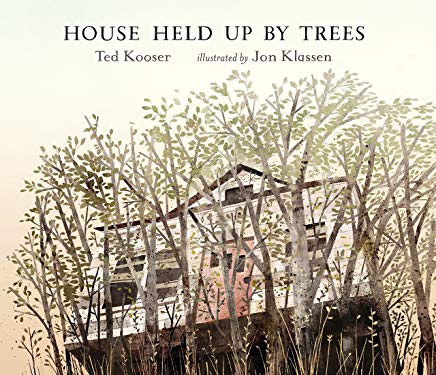

In House Held Up by Trees, the poet Ted Kooser has meanwhile populated Klassen’s brown and white landscapes with questions that do not seem to promise any rousing resolutions (“Wait! I have seen my hat!”), but manage to nevertheless keep you guessing about what should happen when all that white (the perfectly tended lawn that frames the house of the title) and all that brown (the wooded, wild acres of adjacent plots) inevitably inch together. This despite the Sisyphean ministrations of the father here, mowing and pulling up seedlings and stumps, while the children take shelter in the cool of the shadows, crawling on hands and knees, and imagining animals they can barely hear.

But children grow up, move away, and even the most militant convictions are usually softened with age. “The awe-inspiring power of nature to lift us up,” is how this book jacket copy explains the consequences here, though I kind of think if there were any extra explaining to do, then Kooser (who did win a Pulitzer once) would probably have done it himself.

How else to make sense of a roadside spectacle like this house yanked up from its roots, except that someone’s careful planning took at turn for the unexpected? In the end this is nobody’s burden – the father’s moved out, For Sale signs go ever unanswered – still hallelujah for the story it leaves behind.