The Blog

Blog Entry

God & Dog, Part IV

Just got back from a run with the dog by the river. Between all of the runners in my family, he probably logs about twenty-five miles a week, and I don’t know what he thinks about it, but we are glad to have him along to distract us from our infinite footfalls. Otherwise there’s the river, and there are geese from which we must occasionally restrain him, and there are dilapidated piers, and willows and rippling natural grasses which were apparently planted to make us think of someplace else. And there are everywhere people on benches bearing witness: to tugboats between appointments, and gulls, and the resonant lapping of the tide against concrete stanchions, and the sideways, floppy breathing of a hot, exhausted hound.

Oh shiny, happy people! Are they sleeping? How in the world could they possibly be sitting so still? All of my years I have lived in envy of such tranquility, until it occurred to me recently – like a bolt of thunder from a sky I wasn’t watching – that it was possibly everything but the most breathtaking scenery which these people were considering, that indeed that was even its value. Sunsets work this way conceivably: yes, they are fiery and fleeting and all that, still I don’t think anyone goes looking by the river for metaphors so much as the sort of defiantly meaningless spectacles which allow us to wonder and wander and babble impractically to ourselves – forget about returning that call.

Here is William Steig, by turns euphoric and pragmatic, writing in Amos & Boris about a stargazing mouse: “Overwhelmed by the beauty and mystery of everything, he rolled over and over and right off the deck of his boat and into the sea.”

His boat drifts away, along with all of the scheming and building and stocking that went into it. That this happens very early in the story means you cannot help wondering where his awestruck interlude will resonate in the plot – but it doesn’t, not explicitly. Which is, I think, faithful to the unknowable spirit of epiphanies, if not the requirements of a classical three-act. You take these moments where you can find them sometimes, without squandering your good fortune on a moral.

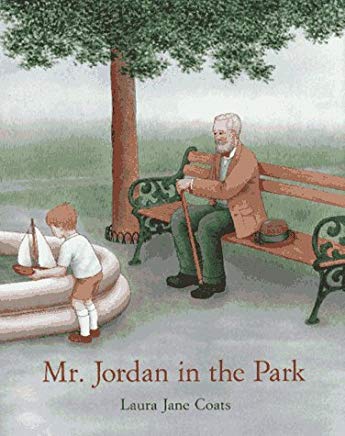

Between racing around a lot recently among errands and drop-offs and pick-ups and rivers, I’ve also been chopping away at the reviews on this site (about five hundred so far from the monolithic six) which means a lot of revisiting generally, and refreshing my memory, and getting to the heart of things in six sentences or less, but of course it does all of these books a disservice to go picking and choosing this way, and I am reminded of the often unquantifiable marvels that drove me to this very particular art form in the first place. Many favorite titles contain such singular moments of reticence at their ends or mysterious middles, and I have piled a bunch up here to the right, though it’s not exactly a category I’m attaching, but a disclaimer, since I suspect that every one of these stories was conceived with an eye for the sorts of gods and deeper meanings we are likely to want to fill in for ourselves.