The Blog

Blog Entry

Kimberley to Khama’s Country

Beloved’s a pretty good word. So’s tamarisk. Promontory. Henceforward. Flailsome. Fulvous. Inordinate. Okay, maybe not Inordinate, which sounds like you might read it where people are pretending to know what they’re talking about, and probably some of the others aren’t even words, but they taste good, don’t they?

Here is a passage from Kipling’s “Elephant’s Child,” describing the journey of that wayward pachyderm:

“He went from Graham’s Town to Kimberley, and from Kimberley to Khama’s Country, and from Khama’s Country he went east by north, eating melons all the time, till at last he came to the banks of the great grey-green greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever trees, precisely as Kolokolo Bird had said.”

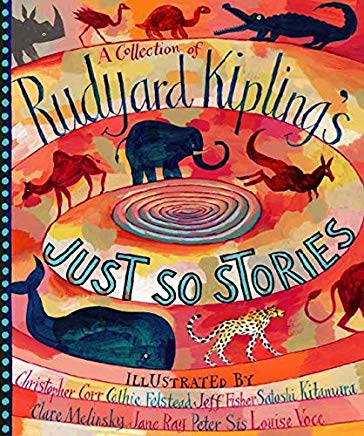

My edition of the Just So Stories is long out of print and, as far as I can tell, nowhere available, replaced for the most part by smaller, thicker editions on higher shelves, with fewer pictures, for older readers. The stories in these newer packagings are almost word-for-word the same. And I do not miss the illustrations necessarily in my disintegrating picture book version, which are warm and simple and striking, and created by somebody named only Nicolas (some crazy Hungarian? Czech?), still there isn’t anything anywhere illustrated to do justice to something as magnificently described as “the great grey-green greasy Limpopo River.” I’m going to trust Kipling on that one, and trust myself, and trust my children to be able to distinguish in their imaginations those fever trees from something called ti-trees, apparently native to primordial Australia, where Yellow Dog Dingo chased the kangaroo into being. Through salt-pans and reed-beds and blue gums and spinifex, through the Tropics of Capricorn and Cancer, “he ran till his hind legs ached.”

Alas though, I miss the picture book format, and perhaps this is only for the resignation suggested by its alternative packaging, that these Just So Stories are somewhere outside of the capabilities of very young readers, too wordy and obscure, too slow and exotically told.

We are often reminded these days how our children are like super-computers, sucking up languages, taking impressions, and constructing impressive full scale models of their future selves where no one can see – all whirring and inexorable – and while I think this ignores the possibility of a lot of stuff that just doesn’t get used, or finds itself discarded or consciously demoted, perhaps there is anyway wisdom in the notion of clearing some wider, more accommodating pathways with wider, more challenging loads. Nobody wants to bore the heck our of their kids, and very smart people can disagree on the specifics, but surely there is an age when Huggly Gets Dressed is every bit as mysterious as “How the Camel Got His Hump” – and surely we should take advantage of it. Because there are some pretty simple stories in this book, and they travel. For fifteen dollars you can pack a single nine-inch volume, and read a very different adventure every day.

This particular existing edition also includes illustrations by a number of very different artists, but the language, at least, stays the same. Perhaps that’s intimidating, yet I think it’s fair to wonder if it isn’t as often parents who are by put off by florid or Victorian-sounding sentences as their children. And words: I used to know a mother who worried specifically over some of Dr. Seuss’s tricked-up vocabulary. All of us have probably met parents who fuss about every manner of responsibility in gloomy, even pathological ways, but this mother struck me then as fundamentally cheerful and conscientious in the matter of educating her son, who was also, in fairness, the sort of kid who liked to incorporate derivations of poo poo into many of his descriptions, and generally needed clear guidance.

So it did not strike me as an unreasonable reservation when I heard it, indeed I still admire the way she even bothered to think it through. But think about this: we are ever bound to come across funny words, and foreign landscapes, and ridiculous greetings, and unfamiliar expressions if we plan to move far in this world. Oh, the Places You’ll Go! remains a wishful, even essential aspiration for our children, but it isn’t dependent on anything as fragile as a hot-air balloon. Sometimes a page is as close as we’re likely to get to a particular destination, though wherever we find it, or recognize it, or imagine it, the view from Kimberley is likely to be clearer if we have visited Khama’s Country first.