The Blog

Blog Entry

Built to Spill

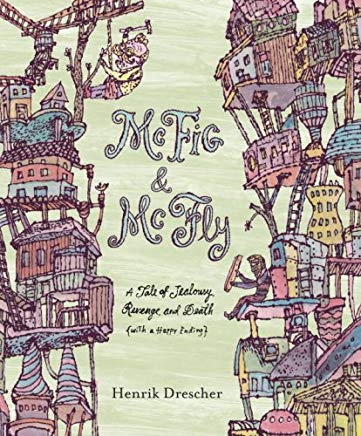

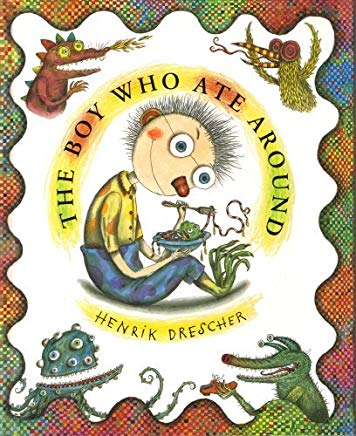

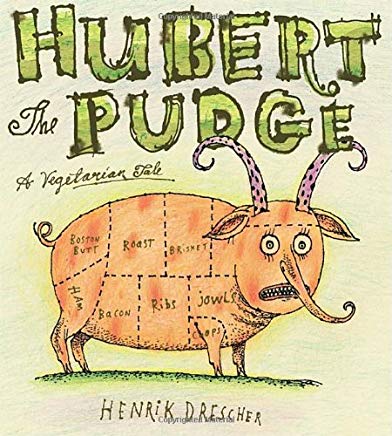

Who doubts Henrik Drescher? Even discounting the prickly pleasures of Hubert the Pudge, A Vegetarian Tale, in which Drescher ends up finishing just about everything he starts; even if you have not witnessed a child consuming his parents in The Boy Who Ate Around, or you are anyway completely unfamiliar with this Danish-born author and illustrator, or Hansel and Gretel, or Grimm’s Fairy Tales generally, or all the bony, creepy fables we have used across human history to keep the children from wandering very far from the tribal hearth; even if you are a skeptic, like me, who sees little red herrings skittering everywhere across the surfaces of our popular culture, and never entirely falls for a title like McFig and McFly, A Tale of Jealousy, Revenge and Death (with a Happy Ending), even then the spectacle of those wild-eyed Scotsmen on the cover should alert you to the possibility that this isn’t your average bedtime confection.

Okay, you’ve been warned. Now delight for ten minutes in this overgrown portrait of basic human ambitions run amok. McFig is the one with the walrusy moustache and mad scientist’s glasses, in case you’re keeping score. McFly you only ever see in profile, with one gigantic eye bulging out of the front of his head, plus a beard that manages to cover every remaining square inch, and blends in nicely with the rest of the landscape here: furry roofs and woolly trees and stubbly pasture – even the sun looks like it could use a shave.

Their parallel striving starts innocently enough, with that walrusy McFig offering to help his recently arrived neighbor to construct a house in the likeness of his own on an adjacent piece of land. Both are widowers, both have young children, and neither seems especially inclined to go frolicking after little Rosie and Anton in all of that underused acreage. There’s time to kill here, between fruit trees and berry bushes and European social security benefits. McFig may seem carefree enough on page one – rocking on his porch and staring vacantly into the middle distance – though in hindsight this begins to look like a cautionary tale about the risks of early retirement.

Absent minds do wander, and convulse, and tie themselves into knots, and alight in some pretty strange places, but they once in a while also produce visions of stunning conviction and originality, and the messy, human truth of McFig and McFly leaves none of these outcomes unexplored. For 142 straight days the two Scotsmen labor tirelessly at getting that neighboring cottage perfectly, identically right, then pause to finally share a single reflective evening together with the children roasting sweet potatoes and admiring their handiwork, like the proverbial broken clock that manages to get the time right once.

Or strangers in the night. Pretty soon McFly is adding a scenic little turret to his roof, and the rest is gritted smiles and feats of engineering to haunt Dr. Seuss. It’s all pretty joyless. Oh, once when McFly is shown testing a newly constructed bungee jumping platform, a manic little smile interrupts his monolithic beard – still nobody ever seems to get very much use from that modular game-room, that glass be-domed tennis court, that second-hand rocket repurposed as a satellite dish. I’d try, and I’d fail, to convey the full scope of their architectural visions, though go ahead and picture flying buttresses and Corinthian columns and eyebrow windows. Now doorknobs made from crusty leather boots, now fishbone-and garbage-can weather vanes.

Those last little flourishes arrive toward the end of construction when McFig and McFly are nearly out of resources, and must resort to bubble gum and spaghetti to hold things together. There’s even one of those pages in the middle of this book which folds out extravagantly to accommodate these twin towers of junk. I usually hate this sort of insert for its gimmickry, and also because it reminds me of too many wrestling matches I have had with road maps, but here it feels vital toward capturing the sorts of endeavors which can often seem sensible in their individual pieces, then suddenly, fatefully bonkers when you take a couple of steps back. That many-storied illustration also features McFig plummeting toward the very resolution that was promised in the title – and his not altogether gratuitous comparison to a piece of ripe fruit.

Perhaps every bit as gruesome are McFly’s final moments – condemned to aimless wandering and nature show reruns without McFig to egg him on. Drescher does try to put a shine on things afterwards by showing us how well little Rosie and Anton turned out. Is this because of, or despite, their dueling daddies? Drescher isn’t saying, but the dismantling of their horrible legacies appears to deliver at least as much joy to the little family that ends up emerging as any amount of misery old McFig and McFly ever brought upon themselves. It is from such folly as any virtue that we chart our singular paths, though who doesn’t wish their better angels could also help them laugh?