The Blog

Blog Entry

Blunderbuss

In the past year alone, dozens of very large naval vessels bearing expensive cargo have been commandeered by small groups of men in speedboats off the coast of Somalia, of all places. Indeed their plunder accounts for something like fifty percent of that nation’s gross national product. Mostly the profit is ransoms, and often the negotiations can go on for months, the captain and crews of those freighters reportedly emerging well fed and uninjured. Why then, against the backdrop of a worldwide economic panic, terror alerts, bombs dropping on villages, of hurricanes and earthquakes, have the guys in the speedboats been in the news so much lately?

Because they’re pirates, that’s why. Probably they’re some nasty pieces of work in their personal lives, but every time I hear one of their spokespeople referring to the continuing health and well-being of their Ukrainian or Filipino hostages, every time I read about their sandwich runs and comical opening bids – what starts out at five- or ten-millions dollars often ends up being settled in the low six figures – well, I cannot help reminding myself the cargos in question are possibly weapons heading to Robert Mugabe, or oil heading from Exxon, and I hope that the pirates do nothing very awful to spoil their relatively harmless reputations.

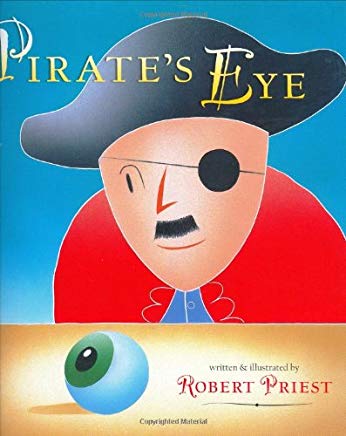

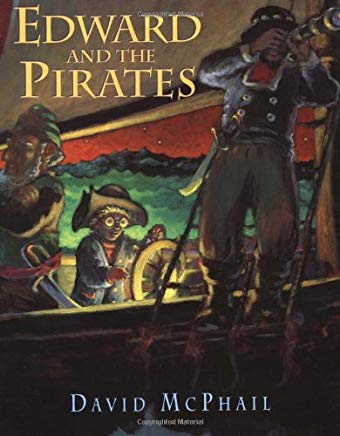

Pirates are the rock stars of children’s literature. In David McPhail’s Edward and the Pirates an enthusiastic young reader checks out a dusty and apparently forgotten book from the library called Lost Pirate Treasure only to find a real live – and illiterate – bunch of pirates waiting for him at home, demanding the book, and finally a read-aloud. In The Pirate’s Eye, by Robert Priest, a salty old dog loses his prosthetic eye while dueling; the eyeball bounces and rolls into the life of a pauper who is able to catch a glimpse of the pirate’s “strange and interesting” experiences, and writes a book from what he sees, which the pirate himself finds on the shelves of his local library.

“How can this be?” growled the pirate. “And how long will it be before they have me in shackles? Who dares tell the story of this pirate’s life!”

I want to believe in pirates like I want to believe in dragons, even though I’m sure the latter would wreak some pretty real havoc if they weren’t actually confined to our imaginations, or history, or Greenland. The appeal of dragons seems self-explanatory – they’re flying dinosaurs for heaven’s sake, armor-plated, fire-breathing, ruby-hoarding, don’t get me started - but why pirates? Why not Vikings or Mongols? Certainly, parts of the costume are easier to pull off at Halloween – think eye patches, hook hands – but I think it’s also because they generally made you walk the plank rather than whack off your head. They had their codes, but also their handicaps – scurvy, typhoons, hook hands – that always made the unsavory details of their profession look like a matter of survival. They got sad. They got drunk. They disappeared. And so we are more or less free, as children and the grown-ups who educate them, to perpetuate a kinder, less menacing legend.

Most of us have things that will immediately turn us off a particular children’s book – things we cannot so easily rationalize. For some it is simply a “message,” though I think in many cases it’s fair to ask if that message is necessarily being sent rather than received. For some the discussion of religion is a problem, and while I do not wholeheartedly share that objection, I get it: God can seem like a bully sometimes.

It’s personal that way, no matter how allegedly enlightened and well connected we are all becoming. And, personally, I don’t like seeing guns in children’s books. I didn’t grow up with them, and so tend to associate them with unnecessary killing, though of course there are people for whom hunting and, I guess, protecting their families remains the most compelling of imperatives.

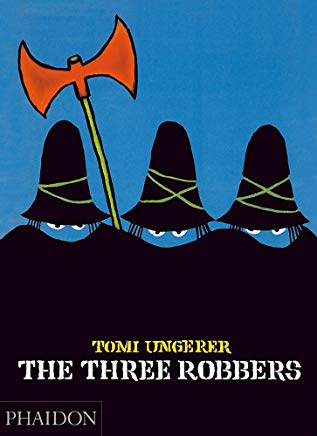

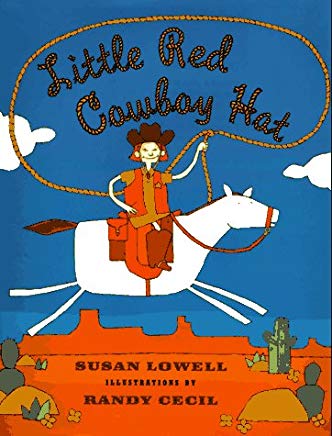

Whatever argument I can muster seems fussy, even semantic by comparison, especially considering I have no problem with daggers and lances and alien lasers and even, in Tomi Ungerer’s The Three Robbers, something called a blunderbuss that is, in fact, a rifle, but more closely resembles a trumpet, which the eponymous robbers use to persuade unsuspecting travelers. I’ve cracked the door also on Little Red Cowboy Hat, about a girl, her grandmother and a very wicked wolf because, well, they’re cowgirls, and their shotgun seems about as metaphorical as the wolf, though of course this is parsing. The world is not an entirely harmonious place, and kids know this, I think – from storybooks wolves, from arguments their parents have on the street, from CNN – though for now it is anyway good to have the pirates to distract us.