The Blog

Blog Entry

Be Cool

Fish gawk, elephants mull, and cows look like they can’t wait for it all to be over. Cats measure. Dogs laugh, grimace, mourn, raise eyebrows, chew the scenery, and otherwise wrangle for our sympathies with operatic range. Dolphins smile - whether this is with us, or at us is never exactly clear – but their cheerfulness appears to derive at least partly from some watery provenance that we can never really know. Chimps cackle, but the joke is most certainly on us.

Penguins? They seem to accept us with heroic equanimity, as though they are even worthy of our scrutiny: Go on about your business, kids. You never hear one of those documentarians intoning, “Then all of a sudden we were descended upon by a furious waddle…” All this while we are compulsively recording their unfathomable to-and-fro marches and childcare hand-offs, their belly-slides and epic devotion to eggs.

In my family we like to toss around ideas about what the next sexy mythical creature will be in pop culture after the whole vampire thing has blown over (Wizards – check. Werewolves – never caught fire, due probably to unflattering facial hair. Elves seem like a good bet: a cool hat or a cool coif would prove sufficient to disguise them), but I don’t think penguins are anywhere close to being eclipsed from among the cast of animal performers in children’s picture books, and this feels like a positive bit of intransigence for a business which seems otherwise inclined to evolve in all of the wrong directions creatively. Of course there is always some danger in over-relying on this – or any – species, still so far the industry appears to be policing itself, either that or it’s harder to write a good book about penguins than it seems.

Who knows what’s going on in those little bird brains? Not, initially, the boy who receives one as a present in Polly Dunbar’s (bravely titled) Penguin. He tries talking to the little enigma, and singing and drawing, and insulting him to get a rise. He tries strapping the penguin onto a rocket and shooting him into outer space, then finally feeding him to a disinterested lion. The lion eats the boy instead, you’ll be happy to know, though an act of typically economical heroism proves mutually liberating in the end – and I’m not going to say any more about it than that.

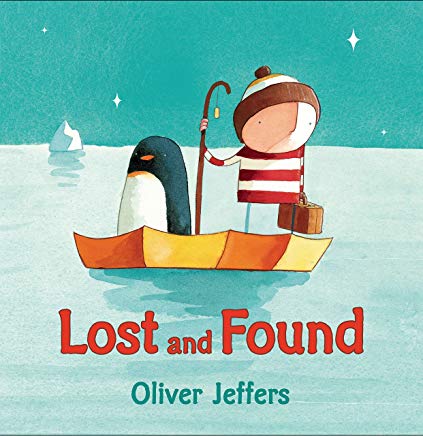

If there is some peril in not finding enough to illuminate the true nature of penguins, then it is doubly risky to try to say too much. I do not care how Dunbar’s penguin got in the box, or who sent it, in fact it seems the responsibility of any good book about penguins to reward our initial leap of faith with the possibility of many mysterious others. In Oliver Jeffers’ Lost and Found the penguin simply shows up on another boy’s doorstep. That this boy appears lonely, nameless, and very often mouthless (like a couple of Jeffers’ other lost boys) speaks clearly to the show-don’t-tell spirit of this story.

This book is beautiful – even shimmery – to look at, and I was skeptical going in; I did not want to be disappointed. “The penguin looked sad,” relates Jeffers, “and the boy thought it must be lost.” Then page to page you hold your breath a little – the boy consulting with birds (who don’t listen), reading a book about the South Pole, launching a rowboat, telling stories, negotiating storms – you think, Dude’s gonna ruin it here pretty soon with an explanation, but you end up making it through, and this story proves worth frequently revisiting for all of its curious reticence. Sad or lost? Sometimes words can’t tell the difference.