The Blog

Blog Entry

Barbarians at the Gate

Among the whoppingly hypothetical questions my children have asked me over the years – How tall is God? How hot is the sun? What’s at the end of the universe? (Walls?) Would you die if you jumped from a roof (probably), or the second floor window (gee, I don’t know), or the third? (Stop obsessing about death.) Who would win in a fight, a lion or a killer whale or a velociraptor? An asteroid or a volcano? What’s your favorite food, favorite day, favorite person, what does it feel like being you? Where does electricity come from? – among all of these insatiable curiosities, the one I felt least qualified sating was How do buildings get built?

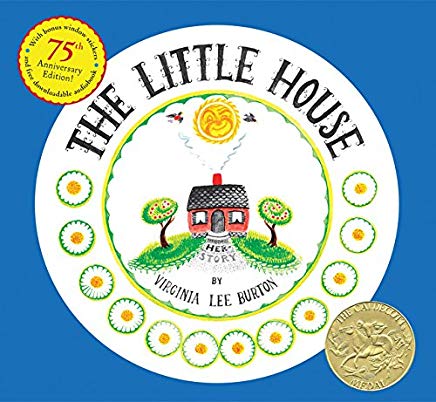

And, lo, the answer was always right between us. Go look at The Little House, I might have responded, and continued following whatever grown-up trail of thought was surely interrupted. We tend to remember this book as a cautionary tale about the wisdom of knowing your place (close your eyes and you might even hear the sound of Scuffy the Tugboat toot-tooting in the background: “I was made for bigger things!”), although I think this neglects Virginia Lee Burton’s irresistible enthusiasm for a city rising up out of nothing.

Yes, gone are the apple trees and the first robins of spring, the pond where the children go skinny-dipping in the summer, the daisies and snowmen and milk cows, yet it’s not very long after their replacement with smoggy brown tenements when Burton, the moralist, surrenders some foreground to Burton, the painter, with here and there a candy-striped awning, a twinkling lobby – even crowds turn the colors of flowers. Here are shoppers and commuters – heck, here are probably tourists – all decked out in their best city finery, here are trolleys, a subway, an elevated train. Here is why we go to all the trouble – now burrowing, now leveling, now stacking new mountains. Sure, it gets ugly sometimes, but sometimes what a bloody miracle. How tall is God? As tall as you can probably imagine.