The Blog

Blog Entry

Then Everyone Was Quiet for a Really Long Time

The cell phone revolution has meant many things to many people, but to me it has mostly laid bare how little we all have to say to each other and how long it generally takes to say it. We are witnesses to these conversations whether we like it or not; if the elimination of background noise is apparently the latest great frontier in telecommunications technology, then how many years before people stop shouting over imaginary crowds?

Turns out what was formerly private is nowhere near as fascinating as I used to believe. Worry really, so I’d call these verbal proliferations a net positive for my personal self esteem. No grand bargains are being hatched where I can hear them now, or philosophical quandaries being considered, or sins forgiven, or misunderstandings completely resolved through some miracles of dialogue I could only ever dream about. I hear talk of babies, of shopping, the flu, I hear grievances replayed, usually for third parties, usually for what sounds like the seventeenth time, and I wonder if the sheer availability of conversation hasn’t diminished our expectations for it, or this wasn’t simply a limit of language all along.

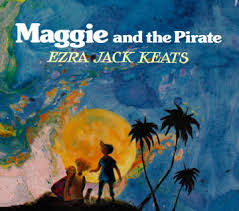

There’s a lot of calling across spaces and stumbling through the dark – both literally and figuratively – in Ezra Jack Keats’s Maggie and the Pirate. Here is an odd one, less Snowy Day than Beasts of the Southern Wild, and as far as I know, Keats never visited this scruffy backwater again. As usual, the kids here seem to live by their own devices, as often, they are surrounded by junk, though in this case Maggie actually lives in it – a broken down school bus on the banks of a river. There is one sparkly new thing amid all the decay – a pink cage that Maggie’s father has built for her cricket which the runty “pirate” of the title promptly hijacks when Maggie and her friends are out shopping for food.

It’s the cage this pirate covets, but the cricket which Maggie wants returned. This she attempts by tacking up signs around the neighborhood which the pirate apparently never sees, still I don’t think even Facebook updates would have reconciled their conflicting motivations. The pirate, for one, doesn’t seem to understand why he has pirated, or at least he fails to make a compelling case, finally emerging from the darkness after a scuffle has resulted in the cricket’s drowning. “My ol man,” he mumbles, not persuasively. “He never makes anything for me. He doesn’t even talk to me.”

If I waited a couple of years to read this to my kids, then I’m pretty sure it wasn’t the death I didn’t think they could handle, but its senselessness. That and the pirate’s final contrition – replacing the old, drowned cricket with a new one – hardly seemed deserving of the tranquility on the final page. Still, what a final page it is: silhouettes against a hugely setting sun, no one saying anything, crickets all around them filling in. Whether you are three years old and gobbling up a hundred new words a month, or five years old and learning a thousand new phrases at school, or thirty-seven and leaving a blaze of communication in hundred-and-forty character increments – when is it ever too early to learn the mercies of sometimes shutting up?