The Blog

Blog Entry

The Stranger

Among the many childish things that I pledged to myself to remember whenever I got around to growing up was the unshakable suspicion of suffering from some terrible handicap that everyone else was always too polite to acknowledge. That, and no one was ever as funny as people pretended. I didn’t see what ha ha ha really had to do with most things.

And so I carry this message forward to my genetic inheritors, indeed children the world over: that you were almost certainly not left here by aliens to report on the eerie congeniality of human kind. And probably not adopted. Probably not the bearer of some original disease.

If I remember this now, it is only because grown-ups were always responding to my misgivings with reassurances like We’ll see, and You’ll understand when you are older – and we didn’t and I don’t, so pure outrage remains my guiding motivation. Though I lack balance, and also the imagination to continue this conversation in a meaningful way, at least I count myself in attendance whenever somebody else should go out on a limb and acknowledge the sort of otherness that is both paralyzing and gives us meaning, a source of grandiosity and sleepless nights – and, yes, in many cases incurable.

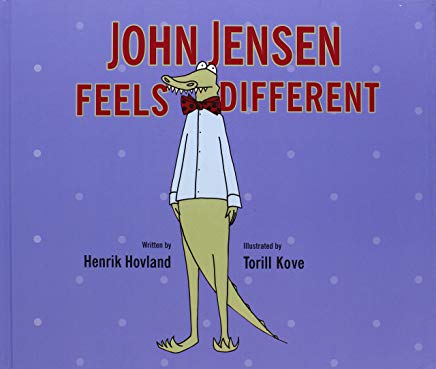

We are not the world, or not all of us; maybe it takes a Norwegian to say it. Mind you, most of the Norwegians I’ve ever met have seemed exceedingly normal and content, but who knows what lurks behind all those endless winter nights and collectivist living? Torill Kove, the illustrator of John Jensen Feels Different confirms my preconceptions of an orderly (too orderly?) district of Oslo, with everyone going about their gently smiling business, not overly concerned that one of their neighbors – on the bus, in the street, in the office – could turn around and just eat them if he were in the mood.

And, boy, is he ever in a mood. Kove and the writer Henrik Hovland get thoughtfully right to the point: before John Jensen even has an opportunity to be a stranger in a strange world, he is a stranger to himself, fretting through his windows onto a deserted street, over breakfast, flossing, the Oslo Times. By the time he boards the bus to his job as a tax accountant, of course he thinks everyone’s staring at him. Nobody is. They’re all too absorbed in their perfectly functional lives.

That John Jensen is a crocodile seems not to be the problem, or a problem, in species-blind Norwegian society. So maybe it’s the bow tie? The only other animal here is an elephant named Dr. Field who attends to John Jensen after he has resorted to concealing his most distinguishing feature beneath something like Spanx. Oh, the cosmetic agonies I have witnessed in my neighborhood! And yet I am not sure I have come across any more poignant ramifications than the sight of John Jensen lying flat on his back in the park – this time everyone does stop and stare – because he did not have the use of his tail to balance with.

“You see strange things in an emergency room,” observes John Jensen with typical wonder, whereupon somebody else takes a dive – a lady, for just being elderly – signaling the shamanic arrival of that Dr. Field. Here is where things might have gone horribly, fatuously wrong, though I found myself attentive to this elephant’s folksy wisdom – “Some people are like this, some people are like that.” – in no small part because this was a book about being different that actually managed to be unpredictable itself. Quick: What is the advantage of having really big ears? For listening? Or for covering your eyes during a scary movie?

And tails?

“Tails are great for tying bows to.”

“Exactly,” says Dr. Field. “Anyone who wears a bow is not afraid of being different.”

“Exactly,” says John Jensen. “Anyone who wears a bow is not afraid.”

Exactly! I hadn’t even gotten to the end of this before I knew I was altogether in agreement, and I’m not even sure, looking back on it now, I know completely what they mean. Still, I pass it along, in the hope our current generation of budding existentialists will get to the bottom of things before they have children of their own. As for John Jensen, I do not suppose his tail is nearly the end of his strangeness, but wish him no sequels, the path to self-awareness being littered with mysterious and unpretty things.