The Blog

Blog Entry

A Dazzle, a Jazzle, a Shine

Autumn is here! Maybe you noticed. Not from the foliage probably, unless you are living in Newfoundland or Alaska – and not for the plummeting temperatures. Still, chances are you meet more people dressed preemptively in corduroy and tweeds as though there were always some appointment just around the corner which they were terrified of missing. Halloween decorations (and Halloween picture books) started appearing in storefront displays around the first of September, Starbucks began peddling their pumpkin spice pick-me-ups on ninety-degree days, and movie critics have already been writing about this year’s Oscar contenders for months before they hit the screen. Can’t we just skip to November already? Climate change aside, there’s something a little strenuous about defining this season which does not reliably define itself.

Remember the kid back in high school who always showed up after the summer with a different wardrobe or hobby or haircut? There’s a shadow of that in the arts this time of year, in music and movies, in theater and TV, still nowhere are these reinventions so morbidly fascinating as the business of books, which always seems to be on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

So let’s pack up our trail mix and slip on our waders for a long day’s journey behind short-term bottom lines – amidst towering escarpments of Fancy Nancy’s latest iteration past Ladybug Girl and Lollipop Fairy – with the hope of discovering some wild thing on the loose, here in this season when almost nothing ever happens by accident.

To Barnes & Noble then: beloved destination, taste-maker, heart-breaker, toy store and stationery outlet, shepherd and sheep, last hope and inscrutable quasi-monopoly (when you think about it) now that Borders bit the dust. More than half of the books you may actually touch before purchasing in this country are the property of Barnes & Noble, still ask by what reasoning a particular title has arrived on its shelves, or remains, or ascends to a throne near the front, and you are likely to elicit a shrug: “Corporate,” this says, without saying it. Which other businesses operate with quite this level of personal unaccountability? Dead businesses. And we are left to wonder about what battle-scarred landscape should emerge.

It’s fun to imagine. Take away one monolithic fetish for the last big thing, and the books that reach kids in the future are conceivably those that won’t look like everything else. Which would seem to bode well for such illustrators as Stephen Gammell whose latest, Laugh-Out-Loud Baby, is a characteristically riotous affair. The great Tony Johnston chips in with a jazzy, improvisatory outline – a baby laughs, his family decides to celebrate with a party, baby forgets what was so funny in the first place, the party continues regardless – though it’s finally the spectacle of all those “crinkly grandmas and wrinkly grandpas” laughing and cooking and drinking and playing instruments and looking positively electrocuted which proves weirdly contagious. Scary? Just a little. Try thinking of this from the baby’s point of view.

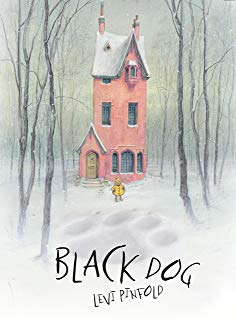

It being more or less the season, perhaps you are even in the mood for some scares. You’d rather cute witches? In contrast with most of Halloween fare which you are likely to have mistaken for greeting cards on the way in, newcomer Levi Pinfold writes, illustrates, and very nearly animates the story of one young family barricading itself into a house against the advances of an eponymous Black Dog. This book evokes one of those classical renderings of The Night Before Christmas – so cozy are the interiors, so tempting to hang out in your pajamas all day – though Pinfold has in mind a very different sort of mythmaking here: namely the seeds of hysteria which can spread between too many like-minded people who need to get out more.

Extrapolate this how you will – I like to picture Birthers huddled together over Fox News – but what’s finally worth revisiting about this otherwise rudimentary little fable is all of the clutter piled up in the margins. Sure, the story turns pretty predictable about one-and-a-half minutes after walking through the door, but get a load of those ornamental owls arrayed mysteriously across the dresser, the knitting on the armchair, the toy octopus who seems to show up in every room. Here scattered crayon drawings, there miniature hot air balloons bumping across the ceilings, and look – is that a Wild Thing peeking out from behind a pillow? Somebody actually lives in these drawings, indeed here is the sort of attention to detail one associates with stop motion movies these days, so it’s hard not to feel a little grateful when an artist this obviously talented should spend his attentions on this form. Levi Pinfold, whoever you are, welcome to the party. Please stay awhile.

The Great Moon Hoax, by Stephen Krensky and Josée Bisaillon, was apparently published in 2011 by Carolrhoda Books, a division of a division of something or other, which I am nevertheless inclined to view fondly owing to their advocacy of Chris Monroe’s Monkey with a Tool Belt series. Someone over there must know what they’re doing. Anyway I missed it, and so did you, but there are a couple of copies left over since who-knows-when (not B&N salespeople), so in this, the most flexible of seasons, let’s pretend the whole last year never happened. Here is another book touching on hysteria, this one a matter of historical record: In 1835 The Sun began publishing a series of articles about the discoveries of an astronomer based eight thousand miles away in South Africa, who was allegedly training his super-powered telescope on the surface of the moon and finding bluish, bearded bison, upright walking beavers, diaphanous man-bats and an “equitriangular temple, built of polished sapphires.” The story is further related by two orphan paperboys who shout themselves hoarse in the streets every morning and make a killing – well, thirty-three cents – till the news is revealed as pure fiction.

Was it worth it? The Sun continued to publish for another hundred or so years, the boys remain unjaded – “It was fun to think about,” says one, “and I can still do that. It’s really all about the words. Even if they’re not quite true, they can make us see amazing things.” – and I just spent 17 bucks on a story I can keep telling when newspapers no longer exist.

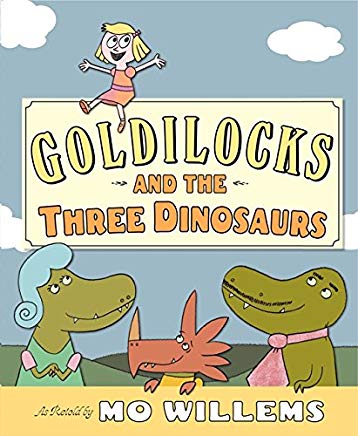

Mo Willems will probably still be writing, even then. In all of his industry (there are books this writer and illustrator probably cannot remember completing) it’s easy to overlook the odd soulfulness (Knuffle Bunny Free), and insurrectionary wit (Naked Mole Rat Gets Dressed) that result when he genuinely applies himself to a readership older than three. In Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs a family of incorrigible predators appears fatefully suspended between cold-bloodedness and denial, amusing themselves with a loud dinosaur noise “that sounded like a big, evil laugh but was probably just a polite Norwegian expression,” a welcome mat subtitled “Tee Hee” and bowls of chocolate pudding cooked at different temperatures “for no particular reason.” Readers may puzzle a little at the meta conclusion – in fact, I think Goldilocks will be clambering up beanstalks in future installments, if Willems has anything to say – but really, we had come about as far as we could with those oblivious bears.

Jon Klassen returns, as he has done a couple of times since the runaway success of I Want My Hat Back this time last year, and great for him, and hilarious, I think, for us. Not that his latest has very much to add to the drama of stolen hats, in fact it has even subtracted stuff (witnesses, sunlight) though if this is ultimately in the service of at least one new direction for American picture books (reticent, carnivorous), then I say Klassen should accessorize the whole animal kingdom before he’s through. This Is Not My Hat turns out to be the sentiment of one very small fish, not puzzled, or angry, or stricken at any misappropriation, but proudly, briefly delighted to have pulled one off.

Do the words Rotational Hydraulic Shears mean anything to you? I’m not sure what makes one Junior Contractor story better than any other. Tractors, backhoes, garbage trucks – they all have a certain charisma, I’ll grant you, which does not extend to a brilliance for talk. Bam. Thud: Sally Sutton’s and Brian Lovelock’s Demolition gets right to the onomatopoeias, and while I may have just been in a smash-em-up mood from my rummaging, there was something by turns a little thoughtful between all of the cathartic tearing and slashing and slamming – a wrecking ball, pleasingly, but also steel-sorters and stone-crushers and wood-shredders so nothing goes to waste. Yesterday’s obsolescence becomes tomorrow’s public work, so perhaps it was a little of that potluck optimism left over from Laugh-Out-Out Baby, or perhaps it was the appearance of a playground in the end. You could describe this as uplifting if you were a critic, or enchanting when you were not personally enchanted, but what do you call that part of enthusiasm which is impossible to pretend?